In this chapter:

- Prevalence of malnutrition

- Causes of malnutrition

- Consequences of malnutrition

- Malnutrition screening

- Improving nutritional status

- The importance of hydration

- Low-intake dehydration

- Improving hydration status

- Monitoring fluid intake

“The Developmental, economic, social and medical impacts of the global burden of malnutrition are serious and lasting, for individuals and their families, for communities and for countries.”

World Health Organisation

Good nutrition and hydration are essential for all. It is of the utmost importance throughout the entire lifespan, from in utero to older adults (1).

This document provides guidance on best practice and auditable standards, with the aim of ensuring nutritional requirements of all individuals in healthcare settings are met.

Food provision is essential to the prevention and treatment of malnutrition. The term ‘malnutrition’ includes undernutrition (wasting, stunting, underweight), inadequate/excessive vitamins or minerals, overweight, obesity and diet-related diseases (2).

Patients can be classed as being either nutritionally vulnerable or nutritionally well. To meet the nutritional needs of all patients, healthcare menus must be able to cater for both the nutritionally well and the nutritionally vulnerable. Assessment of the nutritional content of healthcare menus is essential. See Chapter 11 for how to analyse a menu’s capacity to meet the nutrition standards (outlined in Chapter 10) for both nutritionally well and nutritionally vulnerable patients.

Nutritionally well: An individual with normal nutritional requirements and normal appetite or those with a condition requiring a diet that follows healthier eating principles

Nutritionally vulnerable: An individual with normal nutritional requirements but with poor appetite and/or unable to eat normal quantities at mealtimes, or with increased nutritional needs.

The purpose of this chapter is to highlight what makes individuals nutritionally vulnerable and outline what food services can do to support this patient group.

Prevalence of malnutrition

The World Health Organisation (WHO) states that globally 1.9 billion adults are living with overweight or obesity, while 462 million are underweight, giving rise to economic, social, developmental and medical burdens (2).

Within the UK it is estimated that undernutrition affects over 3 million people, of which 1.3 million are aged over 65 years (3). The British Association for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (BAPEN) 2018 states that most of these cases (93%) are individuals living in the community (3). BAPEN Nutrition Screening Week Survey (4) in 2021 showed:

- 60% of patients admitted to care homes are at risk of malnutrition

- 30% of patients in their own home are at risk of malnutrition

- 34% of patients in community/rehabilitation hospitals are at risk of malnutrition

- 38% of patients admitted to hospital are at risk of malnutrition

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) Clinical Guideline CG32 (5) states that nutrition support should be considered in individuals who are malnourished, as defined by any of the following:

- A body mass index (BMI) of less than 18.5kg/m2

- Unintentional weight loss of greater than 10% within the last 3-6 months

- A BMI of less than 20kg/m2 and unintentional weight loss of greater than 5% within the last 3-6 months

Causes of malnutrition

Malnutrition often results from consequences of malabsorption of nutrients, altered food intake, increased nutrient losses, or altered metabolic demands (6). There are many social, physical and medical factors which contribute to an altered food intake (Table 1.1).

Table 1.1: Factors that increase the risk of poor nutrition/nutritional vulnerability

|

Social Factors |

Physical |

Medical |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

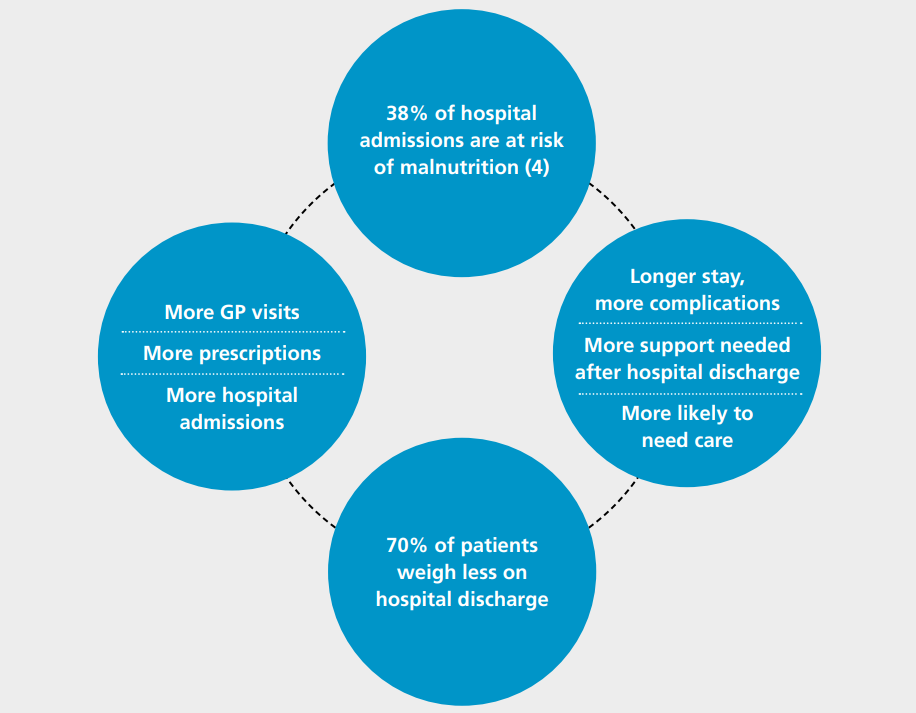

If an individual is unable to provide themselves with adequate nutrition and becomes malnourished, they are more susceptible to disease. This can cause further deterioration, impairing their recovery. This is vicious circle is demonstrated by the ‘Malnutrition Carousel’ (3) (Figure 1.1).

Consequences of malnutrition

There is evidence to show that patients who are malnourished have higher mortality rates and stay for longer in hospital. This can be due to a number of negative effects that malnutrition and dehydration can have on the body, which can include (3):

- Muscle mass loss and deconditioning, leading to an increased risk of falls

- Reduced ability to fight infections and impaired wound healing

- Inactivity and reduced ability to self care

They may also have psychosocial effects including apathy, depression, anxiety and self-neglect (6). All of the above have an impact on both the individual’s quality of life, as well as the quality of life of their families/carers.

Swift action is necessary to prevent an individual’s physical decline secondary to decreased nutritional intake. This decline can be exacerbated by illnesses and any associated clinical interventions. Malnutrition can be life-threatening if poor nutritional intake or an inability to eat persists for several weeks (5).

Figure 1.1: The Malnutrition Carousel (3).

Malnutrition screening

Nutritional vulnerability is more likely to affect those in healthcare settings and requires early detection. Screening for malnutrition should be completed on admission to hospitals to identify high risk individuals and ensure a nutrition care plan is in place. The instigation of a nutrition care plan is a clinical role, and it should support the assessed needs of the patient (7), along with initiatives to address underlying causes (8).

There are a range of tools to support the detection of malnutrition in different groups (9), including:

- Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool (MUST)

- Screening Tool for Assessment of Malnutrition in Paediatrics (STAMP)

- St Andrew’s Nutrition Screening Instrument (SANSI) in mental health settings

- the Patient Association Nutrition Checklist in community settings

Those identified as at high risk of malnutrition through a malnutrition screening programme should be referred for specialist dietetic advice via locally agreed pathways. The dietitian will assess those at risk and create treatment plans based on individual needs.

Improving nutritional status

NICE (5) states that in most cases, an adequate nutritional intake can be provided via ‘good food’ in combination with any additional support needed, such as physical support with eating. However, Age Concern (10) reported a lack of appropriate food provision and absence of support with eating and drinking as one of the most frequently raised issues by older adult’s relatives following a hospital admission. The 2018 Adult Inpatient Survey found that 18% of patients in hospital who said they needed help to eat their meals did not receive the necessary help from staff (11).

The Care Quality Commission (CQC) fundamental standards (12), include good nutrition and hydration. All care settings are expected to provide individuals with adequate nutrition to sustain good health. The Malnutrition Task Force raises awareness and provides information and practical guidance to help combat preventable under nutrition in later life (13). Some initiatives to improve patient’s nutritional status are listed below:

‘Making mealtimes matter’ or ‘Assisted mealtimes’

Clinical areas are often extremely active places with several competing priorities, which can lead to interruptions to patient meals. The National Patient Safety Agency (NPSA) (14) recommended that non-essential activity should stop at mealtimes and all meal service activities should become the clinical priority. Hospital Trusts historically have referred to this as ‘Protected Mealtimes’, but we now acknowledge the importance of not only protecting the time, but also making the environment suitable and having an adequate amount of support available (e.g., with mealtime set up and assistance with eating and drinking).

At mealtimes, all ward activity should focus on the meal service and there should be an awareness of key issues in the eating environment (15,16). Clinical staff should ensure the environment is suitable for eating before the meal is served and that the patients are alert and ready to eat.

A sample protected mealtimes policy, developed in conjunction with the Royal College of Nursing (RCN), is available on the Hospital Caterers Association (HCA) website (17) and multiple Trusts have publicly available policies online.

Adapting the mealtime environment for patients living with dementia

Individuals living with dementia may experience problems with eating and drinking. There are multiple reasons this may happen; they may forget to eat and drink, have difficulty preparing or opening food and drinks packaging, have difficulty recognising food items or have a change in taste or appetite (18). The Social Care Institute for Excellence (19) suggests some additional approaches to encourage oral intake in individuals living with dementia, including offering small frequent nourishing meals/snacks, offering finger foods, using visual aids for meal ordering and minimising distractions at meal times.

Communicating preferences and needs

On admission, all patients should be asked about their food preferences and needs. All allergies and special diets should be noted in their medical records and communicated with catering staff on the ward. This should be recorded to ensure all relevant staff are aware and the patient is provided with the most appropriate menu or food for their needs.

Patients’ food preferences should be understood by the catering team, both on an individual level and as a wider view of population needs/preferences. This should be considered when planning menus, as detailed in Chapter 9, to provide the most appropriate options for patients to choose from.

Nutritional support

The fortification of food is one way to provide nutritional support to patients. Nutrient dense foods, such as skimmed milk powder, cheese, nuts and nourishing drinks can be used to enhance the nutrient content of other foods without increasing their volume. Food based methods, as shown in Table 1.2, are strongly encouraged as a first-line approach. These approaches have been shown to positively impact a patient’s nutritional status (20) and can be used in a variety of settings.

Oral nutrition support should consider micronutrients in addition to energy and protein. It should be noted that when using skimmed milk powder to fortify foods there are two types: one is a ‘skimmed milk powder with added vegetable fats’, the other is a ‘full dairy skimmed milk powder’. The full dairy skimmed milk powder will add more protein to the fortified product when compared with fortification with a skimmed milk powder with added vegetable fats.

Table 1.2: Food based approaches

|

Food based approaches |

|---|

|

Nutrition champions

The aim of a nutrition champion role is to work with all staff to improve the nutrition and hydration care of patients. Nutrition champions are ward-based and may be either a registered nurse or clinical support worker. Nutrition champions work towards strengthening the collaboration between clinical and catering staff. They ensure that nutritional care goals are shared, understood and actioned (21).

Any staff undertaking a nutrition champion role should be offered ongoing support, both from the senior staff on the ward and clinical educators (who may be from organisational learning, corporate nursing and/or the nutrition education lead).

Home from hospital food packages

Some Trusts work alongside local councils and charities, such as Age UK and The British Red Cross, to support initiatives that provide vulnerable patients with small food packages on discharge from hospital. These patients may be discharged to an empty home, with out-of-date food in the fridge and may not have family or a support network nearby. Food packages can often contain coffee, tea, long-life milk, soups and biscuits. This intervention can allow individuals time to organise a more substantial food supply at home.

Home delivered meal services

Meals on Wheels began in 1943 by delivering hot meals to those who were unable to prepare or purchase their own meals. In 2022 there are now multiple suppliers of home delivered meal services, both private companies and local public authorities or charities. Suppliers may provide hot, ready to eat meals, chilled meals which are ready to be microwaved or a frozen meal service.

Such services allow individuals to maintain their independence and remain in their homes for longer (22). The global pandemic has highlighted the on-going need for this crucial form of nutritional support for this vulnerable group.

The importance of hydration

Dehydration describes a deficiency of water (fluid) in our bodies. It is most commonly caused simply by not drinking enough every day (low-intake dehydration).

When a person does not drink enough, the individual cells in the body will start to lose fluids and not work as effectively. This places stress on all the vital organs, with the brain and kidneys being most rapidly affected.

Promoting hydration using low cost or no cost initiatives as part of all patient contact is vital. Staff must take personal responsibility to ensure drinks are always left within easy reach and individuals who rely on carers to access their drinks should be clearly identified (23,24).

Low-intake dehydration

Low-intake dehydration (LID) is the term to help describe the most common type of dehydration affecting older adults across the world (25).

LID is directly caused by a person not drinking enough fluid each day to replace natural water loss, most noticeably in urine and invisible water vapour through breath and skin. LID is not the same as dehydration caused by diarrhoea and vomiting or heavy sweating because it does not include any loss of essential body salts.

When a person is not drinking enough to keep adequately hydrated, the concentration of body salts and waste products in the blood, tissue fluid and cells becomes more concentrated. People of all ages are at risk if they don’t drink adequate fluids, but due to age related factors, such as changes in thirst, older people are most at risk.

LID is unquestionably linked to poor health outcomes and increased hospital admissions (26-30). All older adults in healthcare settings should be considered at risk of low-intake dehydration and encouraged to consume adequate fluids (25).

Table 1.3 outlines the common factors that can contribute to dehydration. Managing these factors alongside staffing issues can provide challenges to supporting and maintaining adequate fluid intake in nutritionally vulnerable patients (31-35).

Table 1.3 Factors that increase the risk of dehydration

|

Social Factors |

Physical Factors |

Medical Factors |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Improving hydration status

To prevent avoidable low-intake dehydration, a vulnerable person of any age or stage of life needs to consistently receive the correct level and type of assistance and encouragement to drink (and eat) based on their needs. This requires a personalised, holistic approach including assessing their reliance on a carer to sit up, undertake mouth care and support their continence. Patients in the last few days of life should be offered regular sips of fluid and/or mouthcare to wet their lips and mouth (36).

To ensure safe and dignified care, the following should be enabled:

- A safe and comfortable position in which to drink

- Offer drinks of their personal choice, made the way they choose

- Place drinks within easy reach and on their best side if applicable

- Use a standard cup of their choice. Only use a drinking aid such as a beaker if assessed as required by clinical team

- The correct level and type of support for assessing with swallowing

- Assistance to hold a drink and encouragement to take extra sips

- Access to their spectacles and/or hearing aid as needed

- For all hot drinks, remind the person it is hot and only leave a drink that is hot if safe to do so

- Always leave a fresh cold drink of the person’s choice within reach

- Where possible promote social interaction opportunities to have a drink together

- Prompt extra sips as part of all other daily contact

Evidence now confirms that all hot and cold drinks count towards hydration, including caffeinated tea and coffee (25). A variety of hydrating drinks should be offered, according to patient preferences. Drinks without caffeine may help reduce people’s concerns about the need to pass urine and/or promote better sleep. Therefore, these drinks should be part of the standard drink offer (25).

Fluid gained from food

Food intake also supports hydration. If a patient is not drinking well, food with high fluid content such as fruits, vegetables, soups, stews and milk-based puddings and jelly should be offered. Nutrition needs should also be assessed, as some of these foods, while high in fluid, are not always nutrient dense.

Use of appropriate drinking aids

There is no national guidance to support appropriate selection of drinking aids. However, the use of spouted beakers is increasingly discouraged as they can increase risk of aspiration and may be considered undignified for adults.

Individuals with swallowing difficulties are advised not to use straws; however, there is no conclusive evidence to suggest that drinking from a cup is any safer (37). To ensure safe practice, the person’s individual speech and language assessments and recommendations should be followed according to local policy.

Monitoring fluid intake

Fluid balance charts or food and drink charts are not always reliably completed. This is a historical problem in hospitals that can result in a patient safety issue. The level and type of monitoring should be based on clinical needs as well as the need for reliable sharing of information within the team and/or for the individual and their families.

Click here to go to the next chapter.

Click here to return to the top of the page.

References

- World Health Organisation. Healthy Diet. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/healthy-diet [Accessed 25th May 2022]

- World Health Organisation. Malnutrition. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/malnutrition [Accessed 25th May 2022]

- BAPEN. Introduction to Malnutrition. https://www.bapen.org.uk/malnutrition-undernutrition/introduction-to-malnutrition?start=4 [Accessed 25th May 2022]

- BAPEN. National Survey of Malnutrition and Nutritional Care in Adults. https://www.bapen.org.uk/pdfs/reports/mag/national-survey-of-malnutrition-and-nutritional-care-2020.pdf [Accessed 29th January 2023]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Nutrition Support for adults: oral nutrition support, enteral tube feeding and parenteral nutrition, [CG32]. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg32/chapter/1-Guidance#screening-for-malnutrition-and-the-risk-of-malnutrition-in-hospital-and-the-community [Accessed 25th May 2022]

- Saunders J, Smith T. Malnutrition: causes and consequences. Clin Med. 2010;10(6): 624-627. https://www.rcpjournals.org/content/clinmedicine/10/6/624 [Accessed 25th May 2022]

- NHS England. 10 Key Characteristics of ‘Good Nutrition and Hydration Care’. https://www.england.nhs.uk/commissioning/nut-hyd/10-key-characteristics/ [Accessed 25th May 2022]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Nutrition Support in Adults. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/qs24 [Accessed 25th May 2022]

- BAPEN. Nutrition screening survey in the UK and Republic of Ireland in 2011. http://www.bapen.org.uk/pdfs/nsw/nsw-2011-report.pdf [Accessed 25th May 2022]

- Age Concern. Hungry to be Heard: The scandal of malnourished older people in hospital. https://www.dignityincare.org.uk/_assets/Resources/Dignity/CSIPComment/Hungry_to_be_Heard.pdf [Accessed 25th May 2022]

- Care Quality Commission. Adult Inpatient Survey 2020. https://cqc.org.uk/publications/surveys/adult-inpatient-survey-2020 [Accessed 25th May 2022]

- Care Quality Commission. Fundamental Standards. https://www.cqc.org.uk/what-we-do/how-we-do-our-job/fundamental-standards [Accessed 25th May 2022]

- Malnutrition Task Force. Eating and Drinking Well in Later Life. https://www.malnutritiontaskforce.org.uk/ [Accessed 25th May 2022]

- National Patient Safety Agency. Protected Mealtimes and patient safety. https://www.dignityincare.org.uk/_assets/Resources/Dignity/OtherOrganisation/Protected_Mealtimes.pdf [Accessed 25th May 2022]

- Burke A. Hungry in Hospital? BMJ. 1997;314:393. https://www.bmj.com/content/314/7078/393.18 [Accessed 25th May 2022]

- Age UK. Still Hungry to be Heard: Seven steps to end malnutrition in hospital campaign. https://www.ageuk.org.uk/bp-assets/globalassets/london/documents/campaigns/still-hungry-to-be-heard.pdf [Accessed 25th May 2022]

- Healthcare Caterers Association. Protected Mealtimes Policy. http://www.hospitalcaterers.org/media/1817/pmd.pdf [Accessed 25th May 2022]

- Dementia UK. Eating and Drinking for a person with Dementia. https://www.dementiauk.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/DUKFS17_Eating_Drinking-2021_March2021.pdf [Accessed 25th May 2022]

- Social Care Institute for Excellence. Dementia: The Eating Environment for people with dementia. https://www.scie.org.uk/dementia/living-with-dementia/eating-well/eating-environment.asp [Accessed 25th May 2022]

- Elia M, Normand C, Norman K, Laviano A. A systematic review of the cost and cost-effectiveness of standard oral nutritional supplements in the hospital setting. Clin Nutr. 2015;35:370-380. https://www.clinicalnutritionjournal.com/article/S0261-5614(15)00142-9/fulltext [Accessed 25th May 2022]

- Bond P. A Hospital Nutrition Improvement Programme. Nursing Times. 2013;109(39): 22-24. https://www.nursingtimes.net/clinical-archive/nutrition/a-hospital-nutrition-improvement-programme-27-09-2013/ [Accessed 25th May 2022]

- Zhu H, Ruopeng An. Impact of home-delivered meal programs on diet and nutrition among older adults: A review. Nutr Health. 2013;22(2): 89-103. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24916974/ [Accessed 25th May 2022] doi:10.12968/bjon.2020.29.1.50

- Davidson J, Folkard S, Hinkley M, Uglow E, Wright O, Bloomfield T et al. A multicentre prospective audit of bedside hydration in hospital. British Journal of Nursing. 2020;29(1):50-54.

- Vourliotis N, Grimshaw K, Harris R. 5 Quality Improvement Project (QIP): A Teamwork Approach to Optimise Fluid Intake in Older Inpatients #ButFirstADrink. Age and Ageing. 2021:50(Supplement_1):i1–i6. doi:10.1093/ageing/afab028.05.

- Volkert D, Beck AM, Cedarholm T, Cruz-Jentoft A, Goisser S, Hooper L et al. ESPEN guideline on clinical nutrition and hydration in geriatrics. Clinical Nutrition. 2019;38(1):10-47. doi:10.1016/j.clnu.2018.05.024

- Budd E. Advisory Committee on Antimicrobial Resistance and Healthcare Associated Infection (ARHAI). Public Health England. Report number: 5, 2013. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/405295/ARHAI_annual_report.pdf [Accessed 25th May 2022]

- Hooper L, Abdelhamin A, Attreed NJ, Campbell WW, Channell AM, Chassange P. et al Clinical symptoms, signs and tests for identification of impending and current water-loss dehydration in older people. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015(4):CD009647. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009647.pub2.

- Department of Health and Social Care. Report of the Independent Review of NHS Hospital Food. 2020. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/929234/independent-review-of-nhs-hospital-food-report.pdf [Accessed 25th May 2022]

- Mustofa ND. Hydration and nutrition concerns among healthcare workers on full personal protective equipment (PPE) in Covid-19 wards. Clinical Nutrition ESPEN. 2020; 40:616. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnesp.2020.09.631 [Accessed 25th May 2022]

- Buaprasert P, Piyapaisarn S, Vanichkulbodee A, Kamson A, Sri-On J. Prevalence and risk factors of hypertonic dehydration among older patients admitted to the emergency department: A prospective cross-sectional study. Geriatrics & Gerontology International. 2021;21(6):485-491. doi:10.1111/ggi.14168

- Lacey J, Corbett J, Forni L, Hooper L, Hughes F, Minto G, et al. A multidisciplinary consensus on dehydration: definitions, diagnostic methods and clinical implications. Annals of Medicine. 2019;51(3-4):232–251. doi:10.1080/07853890.2019.1628352

- Litchfield I, Magill L, Flint G. A qualitative study exploring staff attitudes to maintaining hydration in neurosurgery patients. Nursing Open. 2018;5(3):422-430. doi:10.1002/nop2.154

- Featherstone K, Northcott A, Harden J, Harrison Denning K, Tope R, Bale S et al. Refusal and resistance to care by people living with dementia being cared for within acute hospital wards: an ethnographic study. NIHR Journals Library. 2019;7(11) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK538810/ [Accessed 25th May 2022]

- El-Sharkawy AM, Devonald MAJ, Humes DJ, Sahota O, Lobo DN. Hyperosmolar dehydration: A predictor of kidney injury and outcome in hospitalised older adults. Clinical Nutrition. 2020;39(8):2593- 2599. doi:10.1016/j.clnu.2019.11.030

- Masot O, Miranda J, Santamaría AL, Paraiso Pueyo E, Pascual A, Botigué T. Fluid Intake Recommendation Considering the Physiological Adaptations of Adults Over 65 Years: A Critical Review. Nutrients. 2020;12(11):3383. doi:10.3390/nu12113383

- Royal College of Physicians. Supporting people who have eating and drinking difficulties. A guide to practical care and clinical assistance, particularly towards the end of life. Report number: 2. 2021.

- Pang B, Cox P, Codino J, Collum A, Sims J, Rubin A. Straw vs Cup Use in Patients with Symptoms of Oropharyngeal Dysphagia. Spartan Medical Research Journal. 2020;4(2). doi:10.51894/001c.11591