What is the role of spiritual care in dietetic practice? Registered dietitians are already excellent practitioners when it comes to compassionate care and cultural competence – but can and should we go further? Do we need to better identify spiritual needs, the need for meaning-making and faith support around the challenges our service users are grappling with, as they try to eat well to manage complex conditions?

What do we mean by spiritual care?

The definition of spirituality is hotly debated, although commonly accepted as: “Spirituality is the aspect of humanity that refers to the way individuals seek and express meaning and purpose and the way they experience their connectedness to the moment, to self, to others, to nature, and to the significant or sacred.” (1 - see references below) For some, ultimate meaning and purpose in life is found through religious beliefs and a relationship with the divine (religious spirituality); for others it is found outside of religion (non-religious or secular spirituality). Spiritual care is considered: “The care which recognises and responds to the needs of the human spirit when faced with trauma, ill health or sadness and can include the need for meaning, for self-worth, to express oneself, for faith support, perhaps for rites or prayer or sacrament, or simply a sensitive listener. Spiritual care begins with encouraging human contact in a compassionate relationship, and moves in whatever direction need requires.”2

Why is spiritual care important in dietetic practice?

Dietitians come across many people who are struggling with a very wide variety of health problems, both physical and mental. They often spend longer with an individual than a medical practitioner does, for example; and during a consultation dietitians probe into lifestyle and habits gaining a very personal insight into a person’s day-to-day living. It is often during these times that emotional needs are raised and dietitians listen compassionately, provide support within their sphere of competence and refer on when necessary.

However, the need for meaning making and faith support may go unnoticed or be side-stepped for fear of saying the ‘wrong thing’ or considering it to be ‘someone else’s job’. In reality, the individual may not be seeing any other health professional, nor have developed the same rapport. So these issues are revealed and, as such, if the dietitian does not address them, they may not be addressed at all. Support may go unnoticed or be side-stepped for fear of saying the ‘wrong thing’ or considering it to be There is growing review evidence suggesting clear and consistent links between religious or spiritual struggles and poor health and wellbeing.3 Spiritual struggles have been defined as follows: “Spiritual struggles occur when some aspect of spiritual belief or experience becomes the focus of negative thoughts or emotions, concern or conflict. It can take many forms including divine struggle doubts around their beliefs); and finally struggles around ultimate meaning (perceived lack of meaning in one’s life).”4

1. Assessment

Anthropometry Biochemistry Clinical/Physical Dietary

Environment/Social/ Behavioural Focussed on service user SPIRITUAL CONCERNS

Questions for spiritual assessment:

- Do you consider yourself spiritual or religious?

- How do your beliefs or values influence what you eat or how you manage/cope with your health?

- Do you have any spiritual or religious concerns at this time?

These can be asked directly at the beginning of a consultation or interwoven within the conversation as difficulties become apparent. A spiritual concern may not be obvious at first but may be revealed as the dietetic consultation progresses. Although question 1 leads into 2. A negative response to question 1 does not preclude a positive response to questions 2 and 3.

2. Identification Problem

Aetiology - IS A SPRITUAL CONCERN CONTRIBUTING? Signs and symptoms

When considering the aetiology to the existence of, or maintenance of the Nutrition and Dietetic problem take a moment to consider the role of spirituality. For example, is an underlying spiritual concern contributing to the problem? Perhaps a spiritual concern is leading to a maladaptive coping behaviour such as binge eating?

3. Plan

What? Overall measurable outcomes & intermediate goals based on diagnosis and assessment. SHOULD ADDRESSING SPIRITUAL CONCERNS BE A GOAL?

How? Interventions to meet goals and outcomes e.g. provision of nutrition support, education package, counselling. WOULD SPIRITUAL OR RELIGIOUS SUPPORT HELP?

Who? Service-user centred, roles and responsibilities of individuals, professionals and organisations required to deliver intervention. WHAT WOULD SERVICE USER LIKE? WHAT SPIRITUAL/RELIGIOUS RESOURCES CAN THEY DRAW ON? REFER TO FAITH-BASED INTERVENTION? OR FAITH LEADER?

If spiritual concerns may contribute to the nutritional problem, addressing these should be planned. For example if anxiety about the eternal destination of a loved one is reducing an elderly widow’s appetite she may benefit from seeing a spiritual or religious leader. It may then be appropriate for the service user to set a spiritual goal of seeing a chaplain, for example, which might ultimately help improve appetite.

4. Implement

This is the action phase.Dietitians may carry out the intervention or delegate or coordinate the intervention delivered by another health or social care professional; patient, client or carer; voluntary organisation; CHAPLAIN, FAITH COMMUNITY OR FAITH LEADER

Depending on the spiritual goal, implementation could involve:

- Dietitian referring to chaplaincy services.

- Service user talking to friends in their own spiritual or faith community.

- Service user talking to a spiritual or faith leader in their own community.

- Service user exploring matters of spirituality and faith, which are of concern to them, either independently e.g. through reading or visiting faith-based websites or through joining a support group.

- Service user using their own spiritual resources of spiritual or religious practices they find helpful e.g. prayer, reading holy scriptures.

- Service user attending a faith-based lifestyle programme which incorporate their beliefs and provides spiritual motivation e.g. Taste & See, a church based programme to help develop a healthy relationship with food19-22.To facilitate the setting of spiritual goals for a service user, a dietitian should have a good working relationship with local chaplains and faith communities so that they can refer to them or provide service-users with a list of contacts or resources they may find helpful. It is advisable to get such a list checked by the chaplaincy service.

5. Monitor and Review

Monitor change in outcome and intermediate goals. ARE SPIRITUAL GOALS BEING MET?

Monitoring of spiritual goals may include; whether or not an appointment has been kept with a chaplain, whether a spiritual matter has been discussed with friends, whether they have attended a faith-based programme or whether they have engaged in the spiritual activity or religious practice that they wanted to do. Goals should be reviewed and adjusted according to changing needs and preferences of the service user.

6. Evaluation

Final measurement against standards or overall outcome. Achieved, partially achieved, not achieved? E.g. HbA1c, weight/centile, dietary goals, confidence in managing diet, reduction in symptom, reduced binge frequency, LESS SPIRITUAL CONCERN

Appropriate questions to evaluate spiritual care needs could be: “Do you have any religious beliefs that were not adequately considered by your treatment?” “Have any spiritual worries or concerns you had about this been addressed?” “Have you been able to take part in any spiritual or religious activities that have been important to you at this time?”

The proposed mechanism by which spiritual struggles lead to poor health is through a psychoneuroimmunological pathway (interaction between psychological processes and the nervous and immune systems). Spiritual struggles may lead to stress and low mood which affects both mental and physical health. Whereas positive religious coping, which encompasses religiously framed cognitive, emotional, or behavioural responses to stress, is associated with a reduction in stress and therefore better physical and mental wellbeing.5 Positive religious coping may help achieve meaning in life, closeness to the divine, hope, peace, connection to others, self-development, and personal restraint.6

Stress and low mood play a role in many health conditions that dietitians treat on a daily basis. A common maladaptive response to these negative emotions is to overeat7 Also, stress and depression is associated with malnutrition,8 it can negatively affect gut health,9 increase cardiovascular disease risk factors,10 and lead to a deterioration in glycaemic control.11

Therefore in extension to the biopsychosocial model of health that dietitians currently use, should dietitians adopt the more holistic biopsychosocial-spiritual model of health12,13 and be more intentional about addressing spiritual and religious needs which may be influencing the health of their service users?

To answer this, a systematic review (awaiting publication) was conducted to ascertain whether there is direct evidence of spiritual or religious needs among dietitian service users and whether dietitians already address these needs. There was medium quality evidence from clinical guidelines and qualitative studies showing unmet spiritual needs among patients receiving dietetic care for a variety of long-term conditions including cancer, COPD, heart failure and diabetes. These unmet needs were present in service users from a variety of ethnicities, religions and those who were not religious.

However, the evidence suggested that dietitians were only involved in addressing issues of faith and meaning-making through multidisciplinary team working when addressing ethical dilemmas regarding nutrition and hydration at the end of life.

How can dietitians address these unmet spiritual needs among their service users?

In other healthcare fields such as nursing, clinical psychology, medicine and palliative care, good practice generally includes screening and referral to spiritual care provider or chaplain.1 The depth of assessment should be conducted according to a clinician’s training and competency. Spiritual screening or triage is a quick determination of whether a person is experiencing a serious spiritual crisis requiring immediate referral to a chaplain. Such screening may be conducted on hospital admission, for example, and may include questions like, “How important is religion and spirituality in your coping?” and “How well are these resources working for you at this time?”14 It is recommended that spiritual distress or religious struggle is treated with the same intent and urgency as treatment for pain and any other medical or social problem.1

Spiritual history taking involves a broader set of questions as part of a holistic clinical assessment by a healthcare provider and aims to open up conversation to empower individuals to draw on their inner spiritual resources as well as identify spiritual distress and refer to a spiritual care provider/chaplain where necessary. While there are a variety of spiritual assessment tools which can be used for this purpose,15 they should not be used as a tick-box exercise but rather to help guide conversation.

A spiritual care provider or chaplain has specific training to undertake a more detailed spiritual assessment, complex spiritual diagnosis and treatment. Some mental health professionals and psychotherapists also have competencies in spiritualty and religiously integrated counselling or psychotherapies.16,17 This in-depth spiritual counselling would typically fall outside the role of a dietitian. Indeed, despite great strides into collaborative person-centred care, an underlying power imbalance between a dietitian and service user likely remains; this means extra care needs taking to ensure there is neither coercion nor judgement on the part of the dietitian with respect to any spiritual or religious belief or practice. This would be an unethical exploitation of a service user’s vulnerable position.

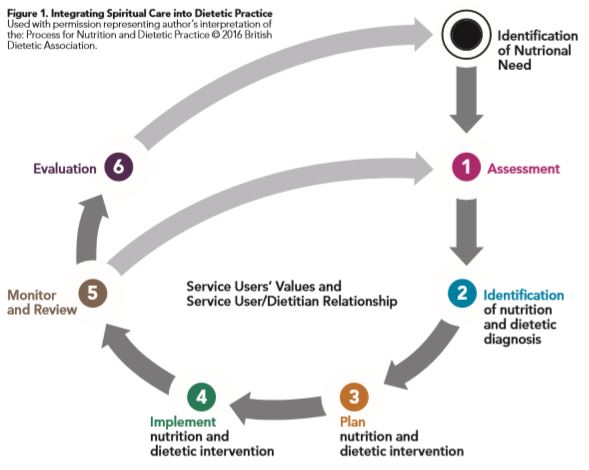

However, enquiring whether a service user has religious or spiritual beliefs that might be helpful or causing them concern at the present time is neither threatening nor coercive. It is this latter practice I would recommend dietitians use to integrate spiritual care into dietetic practice and this can be incorporated into the Nutrition and Dietetic Process for practice18 as shown in figure 1.

In conclusion

There is evidence that dietetic service users have unmet spiritual needs that go beyond compassionate listening and cultural competency. Dietitians can provide appropriate spiritual care for service users, using a model of spiritual assessment, service user-led spiritual goal setting or referral, and evaluation which is easily integrated into the Nutrition and Dietetic Care Process.

About the author

Professor Deborah Lycett PhD RD is Professor of Religious Health Interventions & Dietetic Practice and Theme Lead for Behavioural & Implementation Science Research at the Centre for Intelligent Healthcare, Faculty of Health & Life Sciences, Coventry University.

References:

1 Puchalski, C., Ferrell, B., Virani, R., Otis-Green, S., Baird, P., Bull, J., Chochinov, H., Handzo, G., Nelson-Becker, H., Prince-Paul, M. and Pugliese, K., 2009. Improving the quality of spiritual care as a dimension of palliative care: the report of the Consensus Conference. Journal of palliative medicine, 12(10), pp.885-904.

2 NHS England 2015. NHS England NHS Chaplaincy Guidelines 2015: Promoting Excellence in Pastoral, Spiritual & Religious Care [online] available from <https://www. england.nhs.uk/wp-content/ uploads/2015/03/nhs-chaplaincyguidelines-2015.pdf

3 Abu-Raiya, H., Pargament, K.I., Krause, N. and Ironson, G., 2015. Robust links between religious/ spiritual struggles, psychological distress, and well-being in a national sample of American adults. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 85(6), p.565.

4 Exline, J. J., Pargament, K. I., Grubbs, J. B., & Yali, A. M. 2014. The Religious and Spiritual Struggles Scale: Development and initial validation. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 6(3), 208-222. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/ a0036465

5 Ano, G.G. and Vasconcelles, E.B., 2005. Religious coping and psychological adjustment to stress: A meta-analysis. Journal of clinical psychology, 61(4), pp.461-480. 6 Pargament, K. I., 1997. The psychology of religion and coping: Theory, research, practice. New York: Guilford Press.

7 Adam, T.C. and Epel, E.S., 2007. Stress, eating and the reward system. Physiology & behavior, 91(4), pp.449-458.

8 Zhang, X., Pang, L., Sharma, S.V., Li, R., Nyitray, A.G. and Edwards, B.J., 2019. Prevalence and factors associated with malnutrition in older patients with cancer. Journal of geriatric oncology.

9 Windgassen, S., Moss‐Morris, R., Chilcot, J., Sibelli, A., Goldsmith, K. and Chalder, T., 2017. The journey between brain and gut: A systematic review of psychological mechanisms of treatment effect in irritable bowel syndrome. British journal of health psychology, 22(4), pp.701-73.

10 Barth, J., Schumacher, M. and Herrmann-Lingen, C., 2004. Depression as a risk factor for mortality in patients with coronary heart disease: a meta-analysis. Psychosomatic medicine, 66(6), pp.802-813.

11 Riazi, A., Pickup, J. and Bradley, C., 2004. Daily stress and glycaemic control in Type 1 diabetes: individual differences in magnitude, direction, and timing of stress-reactivity. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice, 66(3), pp.237-244.

12 Sulmasy, D.P., 2002. A biopsychosocial-spiritual model for the care of patients at the end of life. The gerontologist, 42(suppl_3), pp.24-33.

13 Hatala, A.R., 2013. Towards a biopsychosocial–spiritual approach in health psychology: exploring theoretical orientations and future directions. Journal of Spirituality in Mental Health, 15(4), pp.256-276.

14 Fitchett, G. and Risk, J.L., 2009. Screening for spiritual struggle. Journal of Pastoral Care & Counseling, 63(1-2), pp.1-12.

15 McSherry, W. and Ross, L. eds., 2010. Spiritual assessment in healthcare practice. M&K Update Ltd.

16 Vieten, C. and Scammell, S., 2015. Spiritual and religious competencies in clinical practice: Guidelines for psychotherapists and mental health professionals. New Harbinger Publications

17 Pargament, K.I., 2007. Spiritually integrated psychotherapy. New York: Guilford.

18 British Dietetic Association, 2013. A Curriculum Framework for the pre-registration education and training of dietitians https://www. bda.uk.com/training/practice/ preregcurriculum