Dr Claudine Matthews explores the opportunities and challenges underpinning the nutritional management landscape in sickle cell disease through a political lens.

Nutrition in sickle cell disease (SCD) is a neglected part of standard care provision in the UK, resulting in huge variations in nutrition service provision available to patients living with SCD.1 The current nutrition landscape in SCD remains underdeveloped and is defined by poor knowledge and awareness of nutrition, limited resources and poor nutrition service provision2 requiring policy and practice change.1

The lack of nutrition service provision in SCD drives this health inequality, which affects sickle cell patients’ experience, access and outcomes as they are left to self-research, self-diagnose and self-manage their often complex nutritional needs, thereby increasing their risk of late diagnosis of nutritional problems.1 The reduction of health inequalities is a high priority on the health and political agenda in the UK and presents an ideal opportunity to call for nutrition to be placed on the Sickle Cell and Thalassemia All-Party Parliamentary Group (SCT APPG) meeting agenda for open discussion – this took place at the Houses of Parliament on 11 December last year.

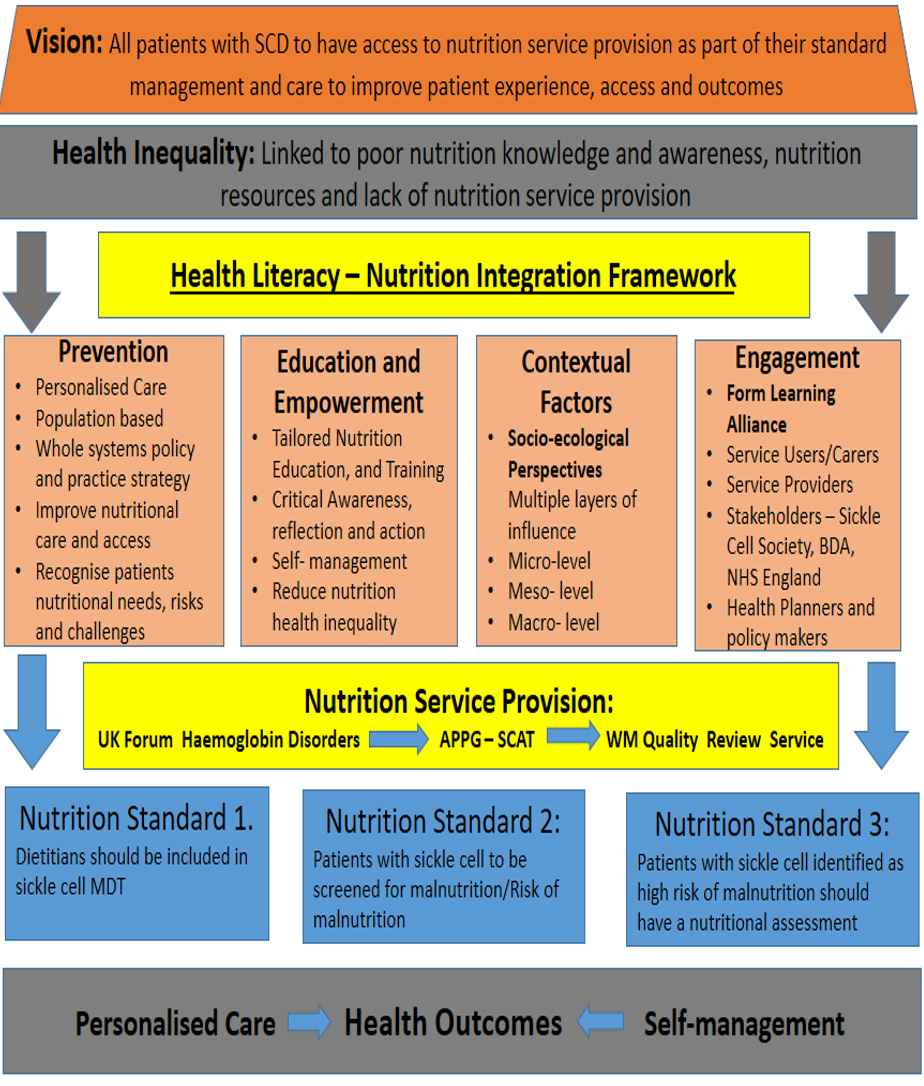

Figure 1: Health Literacy-Nutrition Integration Framework (Blueprint) – Matthews, 2023

What is sickle cell disease (SCD)?

SCD is a marginalised genetically inherited red blood cell disorder3 and is the fastest growing and most common haemoglobinopathy in the UK.4 SCD has both medical and nutritional implications,5 although the medical management takes priority and is well developed.6 On the other hand, the clinical features of the condition are responsible for growth delays, nutritional deficiencies and impaired immunity that require nutrition service provision, yet this remains underdeveloped,6 overlooked and neglected as a management option7 despite the established causative link between the clinical features of SCD.

The three main clinical features8 responsible for these nutritional problems in SCD include:

- Chronic haemolysis – rapid breakdown of red blood cells (16-20 days as opposed to 120 days) resulting in chronic anaemia and fatigue, increased red cell turnover, increased oxidative stress and chronic inflammation

- Vaso-occlusive crisis – blockage of small and large blood vessels, causing an increase in sickle cell crisis and pain, ischaemia and infarction, long-term tissue and organ damage and chronic inflammation

- Impaired immunity – impaired functioning of the spleen, increasing the risk of infection, malnutrition and chronic inflammation.

Failing to link these clinical features to the nutritional implications of SCD has contributed to the oversight in considering nutrition as a management option in the condition and therefore a growing health inequality that requires attention from both a health and political perspective.

Considering a political perspective in nutrition in SCD

The No One’s Listening report3 is the seminal report informing the political and health reforms in the management of SCD in the UK. The report was commissioned following the avoidable death of a sickle cell patient, Evan Nathan Smith, in a London NHS Trust. The report highlighted the marginalisation, invisibility and health inequalities in the medical management of SCD, underpinned by racism, resulting in the poor experiences, access and outcomes of people living with SCD.

There was a strong correlation between the main findings of the No One’s Listening report3 and the findings of my doctoral research project.1 The analysis of the research project data revealed poor experiences, access and outcomes in the nutritional management of sickle cell patients. A key finding of the research project revealed that nearly all the participants (n=18), including sickle cell service users, carers and providers, had to self-research what they needed to know about nutrition in SCD. More significantly, the data revealed that patients had to self-manage their nutritional needs due to a lack of nutrition service provision as part of their standard care.

It is important to note the established causative link that exists between the clinical features of SCD and the medical and nutritional implications in SCD, as previously mentioned. It is therefore plausible to infer that the same problems experienced by the medical management of sickle cell patients as reported in the No One’s Listening report, such as the marginalisation, invisibility and health inequality, are relevant in the nutritional management of SCD. These findings were backed up by the findings of my doctoral research project and reflected in the four main themes1 reported below:

- Theme 1: Invisibility of SCD

- Theme 2: Under-recognised importance of nutrition in SCD

- Theme 3: Lack of priority to nutrition

- Theme 4: Multi-level factors affecting nutrition and service provision

These themes reflect the current nutrition landscape in SCD and the inherent influencing factors that need to be addressed in order to improve nutrition service provision in SCD and, moreover, the access and outcomes of the patients who will benefit from having nutrition service provision as part of their standard care. For this reason, both a health and political approach are required to changing policy and practice guidance to support the development of nutrition service provision in SCD as part of standard care.

Exploring political action in nutrition in SCD

In exploring further political action to support the integration of nutrition into standard care in SCD, following on from my 10-minute speaking slot at the recent SCT APPG meeting, the chair of the SCT APPG was asked to respond to two related questions.

The first question referred to the written parliamentary question about nutrition in SCD (dated 14 March 2023) and the parliamentary response (by Neil O’Brien MP) at that time, reporting the lack of evidence to support the inclusion of nutrition in SCD care.

Chair Janet Daby MP responded, “As Chair of the Sickle Cell and Thalassemia APPG, I appreciate the frustrations felt by many in the sickle cell community with the response of the government regarding the lack of evidence on nutrition as an intervention for the treatment of sickle cell. It reflects more widely on the longstanding lack of prioritisation of NHS service areas for people with sickle cell who have been underserved for decades.”

The second question related to how the SCT APPG is able to provide political action to support the integration of nutrition into SCD care.

Chair Janet Daby MP responded, “The APPG continues to focus on the implementation of the recommendations from the No One’s Listening report. This includes calling on UK Research and Innovation and the National Institute for Health Research to launch dedicated sickle cell research opportunities. Moreover, it is important to begin to build evidence which will support the formation of policy which will in turn lead to improved health outcomes for those who live with sickle cell. To support this endeavour, I would also encourage the British Dietetic Association to consider what steps they can take to generate more evidence.”

It is clear from the above response of the SCT APPG chair that the implementation of the recommendations reported in the No One’s Listening report,3 as it related to the failings in the medical management of patients living with SCD, takes priority. Although there is a correlation between the medical and nutritional management in SCD, as mentioned above, the report does not mention the nutritional needs of sickle cell patients – adding to the invisibility of the nutritional needs of sickle cell patients. However, there is some consolation in that my doctoral research project,1 reflected in the main themes stated above, provides empirical evidence of the existence of the marginalisation, invisibility and health inequality linked to the lack of nutrition service provision available to sickle cell patients – requiring improvement in the access and outcomes of these patients.

Secondly, the SCT APPG chair highlights the call for more research to be conducted in SCD, supported by UK Research and Innovation and the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) – in this way, my doctoral research project findings1 cannot be ignored and therefore add valuable evidence to what is reported in No One’s Listening, albeit that it does not consider the nutritional needs, risks and challenges of people living with SCD. Calls for more research dedicated to sickle cell are critical as long as it also includes nutrition in SCD, as there is a significant paucity of research in relation to the nutritional management and the integration of nutrition in SCD,1 with my research project being the first to consider both of these topics.

Thirdly, with regards to evidence to inform policy and practice change in nutrition in SCD, the focus and aim of my research project was to consider the myriad influencing factors affecting the medical and nutritional management of people living with SCD and to inform policy and practice development. The main output of my research project was the development of the Health Literacy-Nutrition Integration Framework (HL-NIF) blueprint, highlighting the key components needed to support nutrition service provision (see Figure 1). There is an opportunity for the BDA to support the implementation of the recommendations of my research project – which calls for dietitians to be part of the SCD MDT.4 However, this requires commitment to recognising nutrition in SCD as an emerging speciality in dietetics and creating opportunities for more dialogue, education and training, dietetic practice development and research in this developing area of specialism.

Next steps

I am encouraged that this dialogue between me, the SCT APPG and the BDA signals a critical starting point to lay a solid foundation for taking definitive action to provide evidence in support of policy and practice change in nutrition service provision in SCD.

This is a huge problem but also an opportunity to work in partnership and collaboratively towards creating the evidence required to convince both health and political policy makers to consider the urgency of change in the development of nutrition service provision in SCD. Without the ongoing translation of the existing and emerging research linking research to clinical practice, the impetus for change based on evidence practice will remain a neglected area.

More importantly, this will significantly compromise and propagate the ongoing health inequalities, invisibility and marginalisation of the lack of nutrition service provision in SCD, impacting the experience, access and outcomes of people living with SCD. The time for change, however, is now…

References

- Matthews C. Co-developing a health literacy framework to integrate nutrition into standard care in SCD, Doctoral thesis, 2023. Available at: https://aru.figshare.com/articles/thesis/Codeveloping_a_health_literacy_framework_to_integrate_nutrition_into_standard_care_in_sickle_cell_disease/24925884

- Matthews C. A cross- sectional survey exploring the involvement, knowledge and attitudes of Dietitians of sickle cell disease in the UK. Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics. [e-journal] 2016, 29 (1), pp. 40-63. Abstracts from the 2015 BDA Research Symposium, 2 December 2015, Birmingham, UK. Available at: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/jhn.12367/full.

- All Party Parliamentary Group. No one is listening. [pdf]. Sickle Cell Society: London, 2021. Available at: https://www.sicklecellsociety.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/No-Ones-Listening-Final.pdf.

- Sickle Cell Society. Standards for the Clinical care of adults with sickle cell disease in the UK. [pdf] London: Sickle Cell Society, 2018. Available at: http://www.sicklecellsociety.org/wpcontent/uploads/2018/04/Webversion-FINAL-SCS-Standards-GSM-6.4.18.pdf.

- Matthews C. Nutritional implications of sickle cell disease. Complete Nutrition (CN) Magazine. 2021, 15 (6), pp. 46-48. [pdf] Available at: http://www.nutrition2me.com/images/freeview-articles/free-downloads/SickleCellDisease1.pdf.

- Hyacinth HI, Gee BE, Hibbert JM. The role of Nutrition in Sickle Cell Disease. Nutrition Metabolic Insights. 2010, [pdf] 3, pp. 57-67. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21537370/.

- Matthews C. The role of nutritional care in Sickle Cell Disease: A real phenomenon. ACTA Scientific Nutritional Health. 2019, [online] 3 (2), pp.74-80. Available at: https://actascientific.com/ASNH/pdf/ASNH-03-0180.pdf.

- Chakrovorty S, Williams T. Sickle cell disease: a neglected chronic disease of increasing global importance. Archive Disease in Childhood. 2015, 100(1), pp. 48- 53.