The coronavirus pandemic and associated lock downs have caused seismic shifts in the way we all shop, eat, cook and think about food. Consumer trends such as stockpiling, the renaissance in scratch cooking and baking, the spike in use of home delivered take-away apps and an increase in in-home snacking may be transient but some may be here to stay. The reaction to COVID-19 has prompted some to adopt a healthier diet and lifestyle whereas for others, the temptations and boredom of being at home has led to greater indulgences.

In a BDA public survey (15 May 2020 to 22 May 2020), 130 people shared their stories of how the pandemic has impacted on food and eating in households. In reviewing the comments, BDA officers questioned whether these experiences will lead us to make a new relationship with food and public health. The survey recorded attitudes to the nation’s food habits in terms of the psychology of food. Comments seem to have prioritised food as a comfort, affording an outdated ‘naughty but nice’ mentality during lockdown rather than food culture which nourishes our bodies and minds.

Given the varied shifts in attitudes and behaviours related to food, dietitians and other health professionals have a significant opportunity to provide practical behavioural based guidance where mindful eating has been shown to be an effective approach.

Mindful eating is focused not just on what we eat but raises our awareness of appropriate portions, how we eat and why. Moreover, mindful eating is clinically proven to lead to healthier eating habits and to a more positive relationship with food. This article sets out the emerging evidence base, the key benefits and a practical overview.

Why mindful eating can make sense for us all

Mindful eating is a relevant and universal approach. More and more people are using mindfulness for well-being and to balance their lifestyle, with downloads of mindfulness apps like Headspace and Calm increasing five-fold during the first month of the pandemic. The application of mindfulness to eating, so called “mindful eating”,(1 - see references below) can be practised by anyone, anywhere, and by all ages… even during lock-down and beyond! Moreover, mindful eating is weight-inclusive, meaning it is appropriate to all weight profiles while losing weight is not the ultimate goal.2

Because of the positive impact the approach of mindful eating can have, many dietary guidelines now include its behavioural principles to promote overall health. For example, in Germany, mindful eating is included in national dietary guidelines and that by eating slowly and consciously there is a greater enjoyment and promotion of the sense of satiation.3 In Canada’s food guide, being mindful of your eating habits while taking time to eat, noticing when you are hungry and when you are full and enjoying the taste of your food are recommendations included to develop healthy eating habits.4

Where does this approach come from?

Mindfulness as a principle is at the heart of Buddhism practice. It can be defined as paying attention to the present moment or purpose while being non-judgmental on thoughts and feelings.5

Historically, the arrival of mindfulness is attributed to Dr Jon Kabat-Zinn. This Professor of Medicine Emeritus was among the first to investigate mind/body interactions in medicine adapting traditional Buddhist principles of mindfulness. He developed a programme to treat chronic pain and stress-related diseases, called “Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction” (MBSR) in the late 1970s.5, 6

In the mid-1990s, Dr Jean Kristeller, Professor of Psychology at Indiana State University and co-founder of The Center of Mindful Eating, started exploring the application of mindfulness practice to eating, which will become “mindful eating”.

She described this new behavioural approach in the treatment of obesity and eating disorders in the 12-weeks Mindfulness Based-Eating Awareness Training (MB-EAT) programme.7, 8

In 1995, another wellness approach was created by two registered dietitians, Evelyn Tribole and Elyse Reisch, and is known as “intuitive eating”.9 Although these two approaches, mindful eating and intuitive eating, complement each other and have significant overlaps, there are some differences and the terms cannot be used interchangeably. Intuitive eating is considered by Evelyn Tribole herself as “a broader philosophy, which includes physical activity for the sake of feeling good, rejecting the dieting mentality, using nutrition information without judgment, and respecting your body, regardless of how you feel about its shape”.10

The benefits of mindful eating

In research conducted in people with overweight and obesity, mindful eating is shown to be effective in reducing binge eating disorders, improving emotional regulation related to eating and may help manage body weight.14, 15, 16, 17 Compared to controls, participants in the mindfulness intervention showed significantly greater decreases in food cravings, dichotomous thinking, body image concern, emotional eating and external eating.18

Emerging science tells us for the general population:

- Mindful eating can be effective in empowering people’s food choices by de-automating the act of eating, and therefore in promoting a positive relationship with food by making deliberate and conscious food choices19, 20, 21

- Eating mindfully can result in deriving more pleasure from food and being satisfied with smaller amounts, as assessed in sensory-based interventions, by savouring with all the senses21, 22, 23, 24

- Eating mindfully can result in better management of food portions, and as it translates into a better awareness of hunger and fullness, feelings can lead to a lower intake at the present eating time25, 26, 27, 28, 29

Mindful eating principles

Several mindful eating protocols have been developed by clinical researchers, including the following three components that are key to eating mindfully.

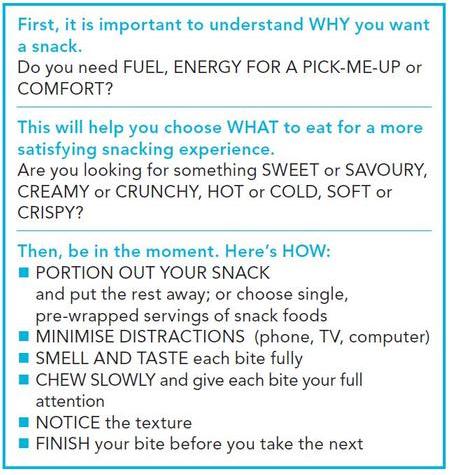

1. Focus on your body’s internal cues and why you want to eat

Mindful eating starts off with checking out your hunger level and being aware of your motivations to eat. You will be able to distinguish between physiological from emotional hunger and external cues that can trigger eating – such as social settings, convenience, routine and time of day. After this internal review, tune into your food preferences at the present moment. Scientific evidence has shown that checking for feelings of hunger and satiety can help control snacking episodes.11, 12, 13

2. Portion your food and pay attention to the eating moment

Once aware of your wants and needs, portion out your food, e.g. depending on your hunger level put one or two biscuits on a plate and put the rest of the pack away and give attention and intention to your eating experience. It is important to avoid distractions such as using the phone or watching TV/screens so that you can focus and appreciate the eating experience and give full attention to each bite and sip.

3. Use your senses to savour foods

Focus on the smells, tastes, textures, shapes and colours of foods to savour and enjoy each bite. The pace of eating should naturally slow down while being in tune to your body. The mindful eating experience ends while noticing either fullness or satisfaction cues.

Resources

Providing clear and practical guidance on mindful eating is particularly relevant at a time when people’s food choices, patterns of eating/snacking, routines and general attitudes towards food have changed.

There are several guides which have been developed specifically for health professionals to use in practice.

These include:

- Scientific monograph supporting the application of Mindful Eating for sensible Snacking practices

- Other resources for health professionals from Mondelez International

References

- The Center for Mindful Eating

- The Center for Mindful Eating Position on Mindful Eating & Weight Concerns

- 10 guidelines of the German Nutrition Society (DGE) for a wholesome diet

- Canada Food Guide

- Kabat-Zinn J. Full Catastropher Living: Using the Wisdom of Your Body and Mind to Face Stress, Pain and Illness. 1990. Delacorte, NY.

- Kabat-Zinn J. Mindfulness-Based Interventions in Context: Past, Present, and Future. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2003; 10: 144-156.

- Kristeller J. The Joy of Half a Cookie. Using mindfulness to lose weight and end the struggle with food. New York: Perigee/Penguin Books. 2016.

- Kristeller J, Wolever R. Mindfulness-Based Eating Awareness Training (MB-EAT): A Treatment Manual. New York: Guilford Press.

- Intuitive Eating

- Intuitive Eating The Difference Between Intuitive Eating and Mindful Eating

- Forman EM et al. Mindful decision making and inhibitory control training as complementary means to decrease snack consumption. Appetite. 2016; 103:176-183.

- Camilleri GM et al. Intuitive Eating Dimensions Were Differently Associated with Food Intake in the General Population-Based NutriNet-Sante Study. J Nutr. 2017; 147(1):61-69.

- Beshara M et al. Does mindfulness matter? Everyday mindfulness, mindful eating and self-reported serving size of energy dense foods among a sample of South Australian adults. Appetite. 2013; 67:25-29.

- Daubenmier J, et al. Effects of a mindfulness-based weight loss intervention in adults with obesity: A randomized clinical trial. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2016; 24: 794-804

- Kristeller J, Wolever RQ, Sheets V. Mindfulness-Based Eating Awareness Training (MB-EAT) for binge eating: A randomized clinical trial. Mindfulness. 2014; 5: 282-297.

- Warren JM, Smith N, Ashwell M. A structured literature review on the role of mindfulness, mindful eating and intuitive eating in changing eating behaviours: effectiveness and associated potential mechanisms. Nutr Res Rev. 2017; 30: 272-283.

- Carrière K et al. Mindfulness-based interventions for weight loss: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2018; 19: 164-177.

- Alberts HJ, Thewissen R, Raes L. Dealing with problematic eating behaviour. The effects of a mindfulness-based intervention on eating behaviour, food cravings, dichotomous thinking and body image concern. Appetite. 2012 Jun; 8(3):847-51.

- Hendrickson KL & Rasmussen EB. Mindful eating reduces impulsive food choice in adolescents and adults. Health Psychol. 2016.

- Camillieri et al. Cross-cultural validity of the intuitive eating scale-2. Psychometric evaluation in a sample of the general French population. Appetite. 2015; 8434-42.

- Gravel K et al. Effect of sensory-based intervention on the increased use of food-related descriptive terms among restrained eaters. Food Quality and Preference. 2014; 32:271-276.

- Hong PY et al. Mindfulness and Eating: An Experiment Examining the Effect of Mindful Raisin Eating on the Enjoyment of Sampled Food. Mindfulness. 2014; 5(1):80-87.

- Arch JJ et al. Enjoying food without caloric cost: The impact of brief mindfulness on laboratory eating outcomes. Behav Res Ther. 2016; 79:23-34.

- Cornil Y & Chandon P. Pleasure as a substitute for size: how multisensory imagery can make people happier with smaller food portions. J Marketing Research. 2015; 53(5):847-864.

- Oldham-Cooper et al. Playing a computer game during lunch affects fullness, memory for lunch, and later snack intake. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011; 93(2):308-313.

- Higgs S. Manipulations of attention during eating and their effects on later snack intake. Appetite. 2015; 92287-294.

- Mittal D et al. Snacking while watching TV impairs food recall and promotes food intake on a later TV free test meal. Applied Cognitive Psychology. 2011; 25(6):871-877.

- Higgs S & Donohoe JE. Focusing on food during lunch enhances lunch memory and decreases later snack intake. Appetite. 2011; 57(1):202-206.

- Robinson E et al. Eating ‘attentively’ reduces later energy consumption in overweight and obese females. Br J Nutr. 2014; 112(4):657-661.