Steph Sloan, Dr Emma Giles, and Jo Smith discuss their work exploring diet quality in people living with severe mental illness via a Public and Patient Involvement and Experience workshop.

People living with severe mental illness (SMI), including schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder and bipolar affective disorder, are disproportionately affected by poor physical health and multimorbidity, particularly in younger populations.1

Early mortality is well documented in people with SMI2,3 who die on average 15-20 years earlier than the general population.4 It is estimated that two in three deaths are related to preventable physical health conditions,5 many of which are diet-related such as cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes and hypertension.

A systematic review6 reported the dietary intakes of people living with SMI to be higher in total calorie and sodium intakes. Patterns of lower fruit and vegetable intake, and higher takeaway, convenience food and sugary drink consumption, were also observed. In addition to poor dietary patterns, people with SMI are frequently prescribed antipsychotic medications, which are often associated with weight gain7 furthering the need for nutritional interventions to be embedded within the care of this population.

However, people with SMI experience several barriers to accessing healthcare, including symptom-related barriers, e.g., comprehension and memory, organisational/environmental issues such as understaffing and lack of reasonable adjustments, stigma and prejudice, low socioeconomic status and perceived non-adherence.8 Where patients with SMI can access diet and weight-related interventions, primary outcomes are often focused on BMI with limited success.9

There is a growing interest in nutritional psychiatry, an emerging field exploring how nutrition can affect brain function and psychological wellbeing. Nutritional psychiatry suggests diet quality may offer a modifiable risk factor in the prevention and treatment of mental illness.10 Proposed pathways include altered gut microbiota,11 inflammation12 and nutritional deficiencies including folate and vitamin D.13

It remains unclear whether nutrient deficiencies are related to poor dietary intake or poor nutrient absorption, and further research is needed.14 Nonetheless, interventions optimising diet quality may offer an attractive therapeutic option for improving physical and mental health in people with SMI. However, there is a lack of information regarding the optimal methods to evaluate diet quality in this population. While various dietary assessment tools such as 24-hour recall, weighed food diaries and food frequency questionnaires can be used, there is limited discussion of their suitability within people with SMI.

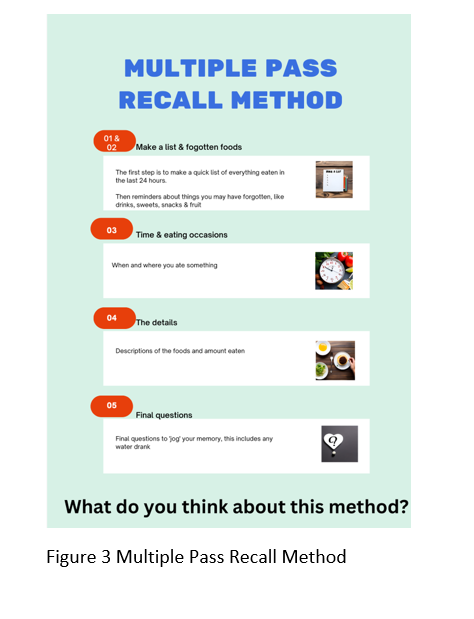

Where difficulties with memory recall, attention, planning and organising may be observed in people living with SMI,15 efficacy of dietary assessment tools must be considered. The multiple pass recall method seeks to minimise participant burden and is used in the Low Income National Diet and Nutrition Survey.16 Compared with other dietary assessment methods, it was found to be favourable in a UK elderly population, where dietary assessment challenges may be similar to that of an SMI population, including memory impairment and carer involvement in food shopping and preparation.17

Aims and method

Widening mortality gaps,3 unsuccessful outcomes within mainstream weight management services9 and increasing interest in the role of food and nutrition in mental health treatments18 emphasise the need to explore diet quality in people with SMI. Therefore, informed by the NIHR Research Design Service’s Community Engagement Toolkit,19 a Public and Patient Involvement and Experience (PPIE) workshop was undertaken to: understand how people with SMI view their diet understand the acceptability of dietary interventions, with a focus on diet quality understand the feasibility of the Multiple Pass Recall methodology in this population.

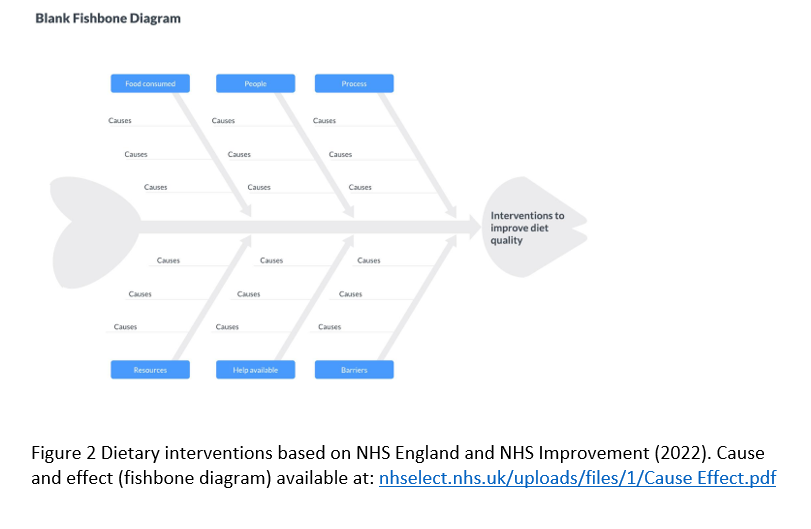

Adults with lived experience of SMI were recruited via a local lived experience group and the workshop facilitated by Teesside University School of Health and Life Sciences and Tees, Esk and Wear Valleys NHS Foundation Trust staff and students. Facilitators used posters (see Figures 1, 2 and 3) to generate discussions relating to workshop aims. Notes were taken on flip-chart paper.

Findings

Four participants attended the workshop with three in person and one online (via Microsoft Teams). Key findings relating to perceived diet quality and acceptability of interventions are presented below.

Diet quality

Awareness of diet quality

Participants were worried about their health and recognised ‘bad habits’ within their diets – knowing what they ‘should’ be eating, but not always putting this into practice. However, some acknowledged that when they are acutely unwell, they may not recognise a change in their dietary intake. Therefore their mental health status influenced awareness of the importance of a ‘good’ diet quality, as well as access to and choices around diet quality itself. Others discussed self-blame or criticism being complicated by hearing voices and an awareness that self efficacy fluctuated with mental health symptoms. Weight and health concerns influenced adherence to medication for some participants, as the potential side effects of weight gain presented an obstacle to their consistent use of prescribed medications.

Influencers of diet quality

Participants highly valued food-related community engagement activities but acknowledged these could be both a barrier and a facilitator to diet quality and health.

Peer support workers were also highly valued in supporting dietary change, particularly where shame or shyness were present, with many acknowledging emotion-led eating that would be easier to discuss with a trusted peer support worker.

A range of social and environmental influences on diet quality were also identified:

- smoking cessation

- time and money

- group dynamics or ‘peer pressure’ to engage in social eating

- long stays in hospital

- degree of cooking skills

Intervention acceptability

Barriers

Participants identified multiple barriers to accessing interventions targeting diet quality, namely environmental or organisational barriers:

- establishing first contact

- meeting referral criterion for the intervention

- lack of specialist support in primary care

- lack of awareness of local service provision

- geographical inequities – namely urban vs rural service provision

- fragmented mental and physical health care

- accessibility, finances, and difficulties with travel due to mobility issues

Suggestions for improvement

Suggestions to make diet quality interventions more acceptable and feasible largely centred around accessibility and community or peer support. Peer support workers were identified again as crucial when considering intervention acceptability. However it was suggested that nutrition education and training could be made mandatory for peer support workers.

Participants acknowledged that group settings can be validating, particularly coming together with a shared interest or passion and lived experience. The idea of creating a shared space for discussing, learning, planning, budgeting, preparing and enjoying meals together was proposed.

Additionally, the concept of providing allotments for individuals was suggested, offering an opportunity to grow and eat nutritious food and promote increased physical activity.

Discussing diet and physical activity together was considered important. Where dietary interventions in inpatient settings were discussed, reducing takeaways was suggested.

Participants acknowledged that sometimes change would only be enacted if facilitated by a carer.

Accessibility suggestions included:

- moving care provision into communities

- ‘right person, right time’ and early intervention

- linking dietary support to existing continuous care provision

- funding for travel

- colours are important for resources, with a preference for ‘calming’ colours such as pastel tones

The feasibility of Multiple Pass Recall as a dietary assessment method

Challenges

As a tool, the Multiple Pass Recall Method was deemed unengaging and potentially intrusive. Difficulties with focus and memory were noted as barriers to efficacy. Wider impacts on care were discussed where participants worried that if they struggled with recall, this may be seen as non-engagement, leading to withdrawal of care. Participants acknowledged the potential for misreporting due to fear of judgement, particularly in the presence of emotional eating.

Suggestions

Participants offered suggestions as to how the acceptability of the multiple pass recall method could be improved. This included offering reassurance and guidance if the person struggled with recall, linking recall prompts to the person’s usual routine and activities, and involving others such as carers or peer support workers in dietary assessment. A suggestion was made to present a list of potentially ‘forgotten foods’ during prompts.

Other suggestions related to dietary assessment more generally, such as a preference for a ‘box-ticking’ approach as with a food frequency questionnaire or a real-time app-based food tracker. An accompanying mood tracker was also discussed to enable a more holistic assessment of dietary intake.

Next steps

Adapting mainstream behavioural interventions to support weight management for people living with SMI may enhance engagement and acceptability.20,21 However, outcomes remain weight focused. With a bidirectional relationship between mental health and diet quality22 and increasing interest in the role of food and nutrition in mental health treatments,18 developing interventions that measure and support diet quality in addition to excess weight should be considered.

Aspects relating to accessibility and community/peer support will be important and challenges around dietary recall should be considered. Workshop findings suggest real-time recording may be more feasible than methods requiring recall. However further research exploring dietary assessment methods in people with SMI is needed.

The project team will use findings from this project to develop a funding application to adapt and develop weight management interventions locally, with the aim of improving diet quality in people with SMI.

Knowledge Booster

- Professionals within mainstream weight management services can consider adapting dietary assessment and intervention for people living with SMI. This can include considering the impact of memory and recall difficulties as well as stigma and shame if utilising the Multiple Pass Recall Method.

- Secondary and tertiary mental health providers can consider offering peer support workers nutritional education and training. The BDA Non-Dietitians Introduction to Nutrition in Mental Health, Learning Disabilities and Eating Disorders, may be appropriate, offering an introduction to nutritional needs and first line management across mental health, eating disorders and learning disabilities.

- Dietitians supporting people with SMI in secondary and tertiary mental health services can consider involving peer support workers in dietetic interventions, acknowledging that service users may prefer to be supported with dietary changes through a trusted peer support worker.

- The food environment – particularly within long-stay mental health inpatient settings – should be considered for dietary interventions to be effective. This includes a particular focus on food-based activities and takeaway consumption.

References

- Launders N, Hayes JF, Price G, Osborn DP. Clustering of physical health multimorbidity in people with severe mental illness: An accumulated prevalence analysis of United Kingdom primary care data. PLoS Med 2022 -04-20;19(4)

- John A, McGregor J, Jones I, Lee SC, Walters JTR, Owen MJ, et al. Premature mortality among people with severe mental illness — New evidence from linked primary care data. Schizophrenia research 2018 Sep;199:154-162.

- Hayes JF, Marston L, Walters K, King MB, Osborn DPJ. Mortality gap for people with bipolar disorder and schizophrenia: UKbased cohort study 2000–2014. British journal of psychiatry 2017 Sep 01,;211(3):175-181.

- Chesney E, Goodwin GM, Fazel S. Risks of all‐cause and suicide mortality in mental disorders: a meta‐review. World psychiatry 2014 Jun;13(2):153-160.

- The Mental Health Taskforce, NHS England. ‘Five Year Forward View for Mental Health’ 2016 (viewed on 1 July 2023)

- Teasdale SB, Ward PB, Samaras K, Firth J, Stubbs B, Tripodi E, et al. Dietary intake of people with severe mental illness: systematic review and meta-analysis. British journal of psychiatry 2019 May;214(5):251-259.

- Wu H, Siafis S, Hamza T, et al. Antipsychotic-induced weight gain: dose-response meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Schizophr Bull. 2022;48(3):643–54. https://doi.org/10.1093/SCHBUL/SBAC001.

- Kaufman EA, McDonell MG, Cristofalo MA, Ries RK. Exploring Barriers to Primary Care For Patients with Severe Mental Illness: Frontline Patient and Provider Accounts. Issues in mental health nursing 2012. Mar;33(3):172-180.

- Stevens H, Smith J, Bussey L, Innerd A, Mcgeechan G, Fishburn S, et al. Weight management interventions for adults living with overweight or obesity and severe mental illness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Nutr 2022 -11-03;130(3):536.

- Firth J., Teasdale S.B., Allott K., Siskind D., Marx W., Cotter J. The efficacy and safety of nutrient supplements in the treatment of mental disorders: a meta-review of meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials. World Psychiatr. 2019;18(3):308–324

- Wallace CJK, Milev R. The effects of probiotics on depressive symptoms in humans: A systematic review. Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2017;16:14

- Chen GQ, Peng CL, Lian Y, Wang BW, Chen PY, Wang GP. Association Between Dietary Inflammatory Index and Mental Health: A Systematic Review and Dose-Response Meta-Analysis. Front Nutr. 2021 May 5;8:662357

- Belbasis L., K.hler C.A., Stefanis N., Stubbs B., van Os J., Vieta E. Risk factors and peripheral biomarkers for schizophrenia spectrum disorders: an umbrella review of meta analyses. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2018;137(2):88–97.

- Teasdale S, M.rkl S, Müller-Stierlin AS. Nutritional psychiatry in the treatment of psychotic disorders: Current hypotheses and research challenges. Brain Behav Immun Health. 2020 Apr 19;5:100070. doi: 10.1016/j. bbih.2020.100070. PMID: 34589852; PMCID: PMC8474162.

- Trivedi JK. Cognitive deficits in psychiatric disorders: Current status. Indian J Psychiatry. 2006 Jan;48(1):10-20. doi: 10.4103/0019- 5545.31613. PMID: 20703409; PMCID: PMC2913637.

- Nelson M, Erens B, Bates B, Church S, Boshier T (2007). Low Income Diet and Nutrition Survey. Food Standards Agency. HMSO: London.

- Adamson, A., Collerton, J., Davies, K. et al. Nutrition in advanced age: dietary assessment in the Newcastle 85+ study. Eur J Clin Nutr 63 (Suppl 1), S6–S18 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1038/ejcn.2008.60

- Grajek M, Krupa-Kotara K, Białek-Dratwa A, Sobczyk K, Grot M, Kowalski O, et al. Nutrition and mental health: A review of current knowledge about the impact of diet on mental health. Frontiers in nutrition (Lausanne) 2022 Aug 22,;9:943998.

- NIHR (2022) ‘Community Engagement Toolkit’. Available at: https://www.rdsresources.org.uk/ce-toolkit (accessed 01/07/23).

- Lee, C., Waite, F., Piernas, C. et al. Development and initial evaluation of a behavioural intervention to support weight management for people with serious mental illness: an uncontrolled feasibility and acceptability study. BMC Psychiatry 23, 130 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-023-04517-1

- Ball MP, Coons VB, Buchanan RW. A program for treating olanzapine-related weight gain. Psychiatr Serv. 2001;52(7):967–9. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.52.7.967.

- Firth J, Gangwisch JE, Borisini A, Wootton RE, Mayer EA. Food and mood: how do diet and nutrition affect mental wellbeing? BMJ. 2020 Jun 29;369:m2382.doi:10.1136/bmj.m2382. Erratum in: BMJ. 2020 Nov 9;371:m4269. PMID32601102; PMCID: PMC7322666.