Using an anonymised case study, Dr Stephanie Fade explains how dietitians can contribute to the care of people with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) dietary guidelines for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)1 imply a limited role for dietitians. However, ADHD related compliance challenges and diet-related co-morbidities e.g. eating disorders, gut issues and obesity, suggest that dietitians should be integral to ADHD care.

For example, meet Annie (not her real name). Diagnosed with ADHD aged 12, Annie’s BMI was on the 98th centile and she struggled with picky eating. Her mother experienced bulimia as a teenager. Annie’s parents read an article about improving symptoms using a few foods diet (FFD) and restricted Annie to meat, vegetables and rice. Annie could not comply and her behaviour worsened.

The psychiatrist advised healthy eating and keeping intake and symptom diaries. Annie did not like the healthy meals offered and took money from her parents to buy snacks. Her behaviour seemed equally challenging all the time.

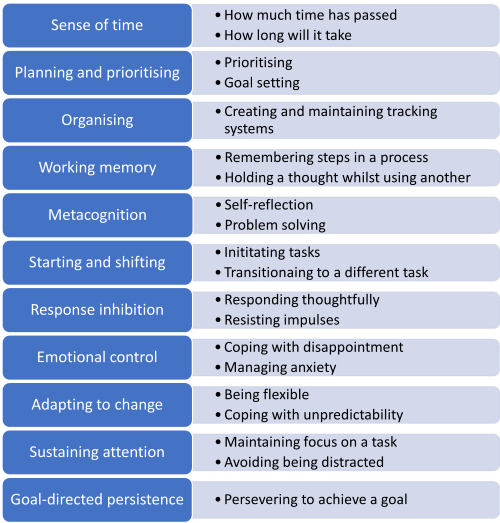

Figure 1: Executive functions adapted from Dawson P and Guare R (2009)2

Annie tried intermittent fasting at university because she felt “disgusted” by her appearance. However, she found herself bingeing in the evenings. Now aged 25, she has been diagnosed with binge eating disorder (BED) and hypercholesterolaemia. When we met, her BMI was 35, she was experiencing intrusive thoughts telling her she was fat and hopeless, and she had intermittent diarrhoea. She was spending £100 per week on supplements recommended and sold by a company that tested her microbiome.

Four things you need to know to help people like Annie

1. Healthy eating can be especially hard for people with ADHD.

ADHD impacts executive functions (EFs). Our EFs are the complex set of mental processes we use to stay regulated and get things done (Figure 1). Annie struggles with impulse control, time blindness and goal setting. She made use of my EF meal planning and goal-setting tools and thinking prompt cards – useful for bringing logical thinking back online when patients are emotionally triggered. I also suggested visual time trackers to help her maintain regular meal times.

ADHD can impact the sensory experience of eating, including awareness of hunger and fullness.3

Understanding a patient’s sensory profile helps personalise advice and partnership with a specialist occupational therapist can be useful. Mindful eating cue cards helped raise Annie’s awareness of feeling satisfied. I also helped Annie start eating vegetables by changing taste and texture using smoothies, soups, air frying and natural flavourings.

Patients who eat an extremely limited range of foods may benefit from working with a clinical psychologist.4 Sometimes they may meet diagnostic criteria for avoidant restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID) and require specialist multidisciplinary help.4

Dietitians can help set out the case for this support. A personalised and often multidisciplinary early intervention approach empowers people with ADHD to eat well.

2. There is some evidence that an FFD helps children with ADHD. However, we need to understand more about responders, and non-responders, and there are significant risks.

A 2017 meta-analysis showed that an FFD, with re-challenge and personalised diversification, can reduce ADHD symptoms.5 Improvements were substantial and professionally validated but were only seen in a subset of patients. Research is ongoing, using bio-markers to explore the characteristics of this subset and the mechanisms involved.6

Excluding preferred foods can risk serious nutritional deficiencies for picky eaters. Annie has a family history of an eating disorder (ED), and Eds are more common in people with ADHD.7 Highly restrictive diets pose specific risks in this context. If, having been made aware of the risks, a patient or family insists that they still want to try an FFD, I always start with intake and symptom diaries. Dietitians can identify links between symptoms and additives/foods that may not be obvious to patients/families. This enables far less restrictive diets to be tested.

Without dietetic support, patients/families often implement restrictive diets independently, unaware of the risks.

3. People with BED should not diet to lose weight. The first line treatment for BED is guided self help.8

A variety of professionals can deliver guided self-help. Our deeper insight into the ‘Eating for Health’ component and our behaviour change skills enable us to offer more specific support to people with diet-related co-morbidities.

I used motivational interviewing skills to raise Annie’s confidence in her ability to change. We have set specific nutritional goals focused on improving Annie’s diet without restriction, including modifying her fat intake and introducing plant stanols/sterols.

Annie is now less focused on weight/dieting, and binge eating episodes are rare. She does not weigh herself but has more energy and her clothes feel looser.

4. Patients can be vulnerable to misleading adverts and testimonials about supplements and special products.

Annie was taking a cocktail of supplements sold by a company that analysed her microbiome from a one-off stool sample. This included separate supplements for iron, magnesium, vitamin D, zinc and high-dose omega 3, a multivitamin, and a probiotic drink with added vitamins. Her intake of magnesium was well above the safe upper limit of 400mg/day.9

I was able to explain the limitations of microbiome testing and the inconclusive evidence relating to supplements for ADHD,1 as well as the risks associated with high doses. I switched Annie to a multivitamin/multimineral that met all her needs in one product. This included adequate vitamin D to correct insufficiency, which showed in her blood results. I also reduced her magnesium intake to a safe level, which stopped her diarrhoea.

We reviewed probiotic products and found a quality product at a lower price. Annie wanted to continue with her omega-3 supplement despite the lack of evidence of benefit, as she hates fish.

Simply telling patients that supplements are not advised may lead them to potentially dangerous, commercially incentivised advice. Dietitians support informed, safe choices.

What next?

Managers: Could this article be a springboard for a business case?

Students: Does this information inspire a dissertation project or even a PhD?

Universities: Could you work with other professions to create multidisciplinary case studies and simulations?

NICE: Could a dietitian bring important insights for the next review of your guidelines?

If you’re interested in continuing the conversation, get in touch via @eatingmindset on Twitter or e-mail [email protected]

References

- NICE Guideline NG87 (NICE 2018a) Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: diagnosis and management. Available at https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng87

- Dawson P and Guare R (2009) Smart but scattered. Guildford Press, New York

- Martin E, Dourish CT and Higgs S (2023) Interoceptive accuracy mediates the longitudinal relationship between attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) inattentive symptoms and disordered eating in a community sample. Physiology and Behaviour, Volume 268, 1 September 2023, 114220. Available at https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0031938423001452

- Thomas JJ, Eddy KT (2019) Cognitive Behavioural Therapy for Avoidant Restrictive Food Intake Disorder. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom

- Pelsser LM, Frankena K, Toorman J, Rodrigues Pereira R, 2017 Diet and ADHD, reviewing the evidence: a systematic review of meta-analyses of doubleblind placebo-controlled trials evaluating the efficacy of diet interventions on the behaviour of children with ADHD. PLOS ONE 12:e0169277 Available at https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0169277

- Stobernack T, de Vries SPW, Rodrigues Pereira R, et al (2019) Biomarker Research in ADHD: the Impact of Nutrition (BRAIN) - study protocol of an open-label trial to investigate the mechanisms underlying the effects of a few foods diet on ADHD symptoms in children BMJ Open 2019;9:e029422. Available at: https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/9/11/e029422

- Nazar, B. P., Bernardes, C., Peachey, G., Sergeant, J., Mattos, P., & Treasure, J. (2016). The risk of eating disorders comorbid with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The International journal of eating disorders, 49(12), 1045-1057. https://doi.org/10.1002/ eat.22643

- NICE Eating Disorders Quality Statement 3 (2018 b) First line psychological treatment for binge eating disorder.

- The Committee on Toxicity of Chemicals in Food, Consumer Products and the Environment (COT) Expert group on vitamins and minerals (2003) Safe upper levels for vitamins and minerals. Available here https://cot.food.gov.uk/sites/default/files/cot/vitmin2003.pdf