Tanya Haffner and Rosie Martin attended the launch of EAT-Lancet Commission 2.0 in Stockholm. Here, they provide some key takeaways, links to resources and reflections on what this can mean for dietitians and healthcare.

The EAT-Lancet Commission 2.0 was launched last month in Stockholm.1 In addition to the main EAT-Lancet report, 72 organisations across the globe, including NHS England, co-developed an Action Brief for Healthcare Professionals,2 being one of ten EAT-Lancet Communities for Action.2

Unhealthy diets continue to be a leading cause of non-communicable diseases responsible for one in five deaths globally, and a major driver of environmental degradation.4,5 The EAT-Lancet Commission first published the Planetary Health Diet (PHD) in 2019.5 It has been one of the most influential scientific reports in the world, with more than 12,000 research citations and over 600 policy citations. This science-based global flexible reference diet was designed to promote human health, which also supports planetary health.

Although the 2019 EAT-Lancet Commission was successful and spurred progress, there was some misunderstanding of and even opposition to its recommendations. This critical feedback has been taken on board, acknowledging that healthy and nourishing food should justly be within the reach of all people. Thus, food justice is the beating heart of the new commission.1 This social foundation drives what the commission suggests is the beginning of a great food revolution – one that could place food systems at the centre of the post-2030 agenda.

The main piece of work for the updated EAT-Lancet Commission,1 conducted by 70 global experts from various scientific disciplines, including health, climate, nutrition, agriculture and justice, was to investigate whether we can:

-

Describe what a healthy diet is, based on the best available evidence

-

Describe the food system’s share of planetary boundaries, in order to set environment targets for food system actors

-

For the first time ever, provide social foundations that allow us to measure progress and understand the status of justice within food systems

Healthy diets

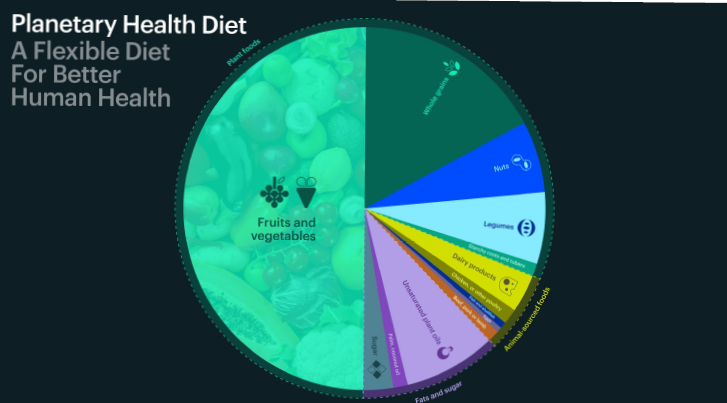

The good news – for those who recognise the PHD – is that when we look at the latest evidence, it is stronger than before, and the recommendations have not fundamentally changed from 2019. The PHD:

-

Remains rich in plants, in which whole grains, fruits, vegetables, nuts and legumes comprise a large proportion of foods consumed, i.e. 87.7% of calories

-

Allows for modest amounts of animal foods including dairy, fish and meat, depending on individual and cultural preferences

-

Limits red and processed meat, sugar and salt due to strong evidence of health risks

-

Puts emphasis on unsaturated plant-derived oils rather than saturated animal fats or palm/coconut oils

The commission emphasises the range of food values, providing flexibility and choice across foods. It is compatible with different dietary preferences, including vegan, vegetarian, pescetarian and omnivore diets, and supports individual, cultural and regional variations.

The emphasis is on the food groups being represented as part of the whole plate, which provides an invitation for individuals and communities to celebrate their own cultures and also an invitation to celebrate the cultures of others.

For the animal source proteins, the commission recognises a range that includes zero values, as there is very good evidence that individuals can be vegan, so long as they ensure they get sufficient plant proteins into their diets.

The commission emphasises that often some of the best examples of the PHD come from the Mediterranean region, North Africa, India, South and South-east Asia and the importance of exploring, enjoying and celebrating different cultures around the globe.

The PHD is based purely on health outcomes, not environmental outcomes. This was the biggest misconception from the first commission. The PHD is based entirely on the direct effects of different diets on human health, synthesised from large cohort studies and meta-analyses.

The commission gave primary consideration to specific direct health outcomes related to insufficient or excessive food intakes versus numerical targets for essential nutrients (e.g. average requirements or EARs). Nutrient requirements were considered but it was highlighted by the commission that these are largely based on small, short-term studies, often not supported by sufficient evidence for long-term overall health. In addition, fats, sugar and salt were considered alongside whole, unprocessed or minimally processed foods. The potential indirect health outcomes relating to antimicrobial resistance, pandemic risk and those caused by environmental changes are discussed in the report.

The commission found that if we are able to shift towards the PHD, we would see:

-

Significant reductions in cardiovascular disease, coronary heart disease, stroke, type 2 diabetes and certain cancers (notably colorectal and lung)1

-

Reduced mortality – 15 million early deaths prevented or 40,000 deaths per day (up to 27% of total mortality) annually1

-

Healthier weights – strong associations with lower obesity risk and better metabolic profiles1

By promoting a variety of plant-based sources of protein, the PHD supports the One Health approach by reducing reliance on intensive livestock production, a major source of antimicrobial use and resistance (AMR).6

| FOOD TYPE | RECOMMENDED INTAKE (grams per day) | RANGE | NOTES |

| Plant foods | |||

| Wholegrains | ~210g or 3–6 servings/day | (20–50% of energy) | 3–6 servings per day of wholegrains over refined grains |

| Tubers/starchy roots | ~50g <1 serving/day | (0–100) | Compared with wholegrains or non-starchy vegetables, consumption of potatoes is associated with greater weight gain & risk of type 2 diabetes |

| Vegetables | 300g or 3 servings/day | (200–600) | Emphasis on a variety of green leafy and dark orange foods |

| Fruits | ~200g or 2 servings/day | (100–300) | Emphasis on a variety of green leafy and dark orange foods |

| Tree nuts & peanuts | ~50g | (0-75) | Consume daily 1–2 servings of tree nuts and peanuts (~50g per day, dry weight) |

| Legumes (beans/pulses) | ~75g | (0–150) | 1–3 servings per day of legumes (~75g per day dry weight) |

| Animal sources foods | |||

| Milk & equivalents | ~250g | (0-500) | If dairy is preferred, consume a moderate amount of one serving of milk (one cup or 25ml of milk) per day or the equivalent amount of milk derivatives (e.g. 25–30g per day of hard cheese) per day |

| Chicken/poultry | ~30g | (0–60) | If meat is preferred, poultry should be prioritised over red meat; moderate consumption of two servings of poultry per week (~30g per day) |

| Fish & shellfish | ~30g | (0-100) | If seafood is preferred, consume moderate amounts of two 100g servings of fish per week (~30g per day) |

| Eggs | 15g | (0-25) | If eggs are preferred, consume moderate amount of two eggs per week |

| Beef/pork/lamb | ~15g | (0-30) | Limit red meat to 1 serving per week or 15g per day |

| Fats, sugars, salt | |||

| Unsaturated plant oils | ~40g | (20–80) | Consume 3 tablespoons of unsaturated oils, including olive, soybean, rapeseed (or canola), sunflower, peanut oil and most other plant or vegetable oils, instead of saturated oils (~40g per day) |

| Palm/coconut oil | ~6g | (0–8) | Limit to maximum of 6g per day |

| Lard/tallow/butter | ~5g | (0–10) | Limit to a maximum of 5g per day |

| Added/free sugars | ~30g | (0-30) | Limit added or free sugars to a maximum of 30g per day, including intake from sugar-sweetened beverages |

| Sodium | <2g (~5g salt) | - | Limit sodium to a maximum of ~5g per day of salt, including intake from manufactured food products |

| Processing | Foods should be mostly whole, unprocessed, or minimally processed |

Table 1: The 2025 Eat-Lancet Commission: The PHD (PHD) Reference Intakes, 2025 (1) EAT-Lancet PHD: Dietary targets for a healthy flexible reference diet for adults, with possible ranges, for a population-level energy intake of approximately 2,400 kcal/day

Nutritional adequacy and considerations

As dietitians, we know that all dietary patterns need to be well-planned to meet requirements. We want to be mindful of several practical and scientific nuances when applying the flexible reference diet. The PHD provides adequate and improved intake of most key nutrients, including fibre, essential fatty acids, folate, magnesium, potassium and zinc. Vitamin B12, iron, calcium and iodine require closer attention when animal source foods are minimal or absent or there is low dietary diversity, particularly for populations with additional nee s such as pregnant women and children.

The commission provides guidance on how different dietary intakes can be optimised.

Vitamin B12: Intake may be low if consumption of animal sourced foods is minimal or absent (e.g. in vegan and vegetarian diets) or in regions which have a less diverse diet. Within the UK and Europe, a fortified supplement is recommended. Obtaining B12 from fermented soya and algae-based foods appears to be sufficient in regions of East Asia.

Iron: Women of reproductive age have additional requirements. Iron-rich legumes such as soya foods and leafy greens, along with vitamin C-rich foods for absorption should be emphasised. The commission supports the WHO’s recommendation for iron supplementation for women of reproductive age, regardless of dietary pattern. Increases in red meat consumption as an iron source, above the recommended ranges of the PHD, are associated with adverse health outcomes and are not recommended.

Calcium: Calcium intake in the PHD is higher than in current diets but may be lower than recommended in some populations. Calcium-rich leafy greens and soya foods including fortified plant milks should be encouraged where dairy intake is low.

Iodine: Intake from current diets and the PHD may be low but largely depends on where food is grown (i.e. soil proximity to coastal environments) and on consumption of seafood and algae. The commission recommends iodised salt for all populations.

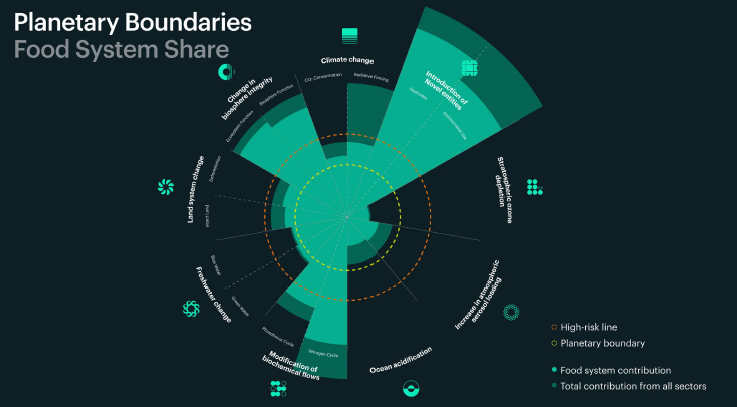

The environmental impact

Foods that are diverse, represent our cultural heritages and nourish both ourselves and our families also nourish our planet.

The commission conducted a full assessment of food’s impact across all nine boundaries. The planetary boundaries, such as climate change and biodiversity loss, are the Earth–system processes that define a ‘safe operating space’ for humanity. Exceeding these limits could lead to abrupt environmental changes that destabilise the planet’s systems.

As a reminder, we have already transgressed seven of the nine planetary boundaries. When evaluated, the commission found that the food system is the single most important driver of planetary boundary transgression.

If we discount food processing and transportation, food accounts for:

-

30% of greenhouse gas emissions

-

80% of biodiversity loss and deforestation

-

37% of land

-

70%–90% of freshwater change

-

70% of the pollution by nitrogen phosphorus

-

25% of ocean acidification

In addition, for the novel entities boundary including pesticides and antibiotics, the food systems have a significant impact.

While the commission is highly concerned about these impacts and recognises that unprecedented ambition is required to return to the safe operating space within planetary boundaries, the good news is that when they looked at how we produce food, what foods we produce and how much we waste food, there is still significant potential to come back within planetary boundaries if we collaborate and act fast enough across the food system.

Shifting to the PHD could reduce environmental impacts, including:

-

Food-related greenhouse gas emissions by 30%–50%

-

Land use by 45%–70%

-

Water use by 25%–35%

-

Eutrophication potential by 35%–55%

Most of these reductions are primarily driven by less intake and production of animal source foods. Environmental impact gains are higher in the more plant-based dietary patterns, such as vegan diets.

Justice

As mentioned previously, the 2025 commission introduced justice. The justice framework, founded in the human rights literature, uses recognitional justice, distributional justice and representative justice.

With these three justices in mind, the commission flags four human rights that they regard as essential to be recognised in food systems:

-

The right to food

-

The right to help the environment

-

The right to decent work

-

Plus one that transgresses all dimensions of justice, the right to freedom and agency

When we consider the significant impact that food has on climate change, on biodiversity loss and on quality and availability of water, the commission urges us all to recognise that we not only have that right but we also have a significant responsibility to ensure that we transition towards healthy diets for all.

When we look at these measures across the dimensions of social justice, it is deeply concerning that too many people fall below what the commission describes as a social foundation, where 2.8 billion people cannot afford a healthy diet. One of the most alarming findings is that only 1% of the global population lives in safe and just conditions. This really emphasises the need for action by everyone involved.

Economic costs and benefits

EAT estimates that transforming the global food system will require about $200 to $500 billion in annual investment.

However, this investment is expected to yield rapid economic returns, avoiding roughly $5 trillion per year in rising healthcare and environmental costs. We already know in the UK from a 2024 study by the Office of Health Economics7 that if everyone in England adopted a plant-based diet, the NHS could save approximately £6.7 billion per year through disease reduction.

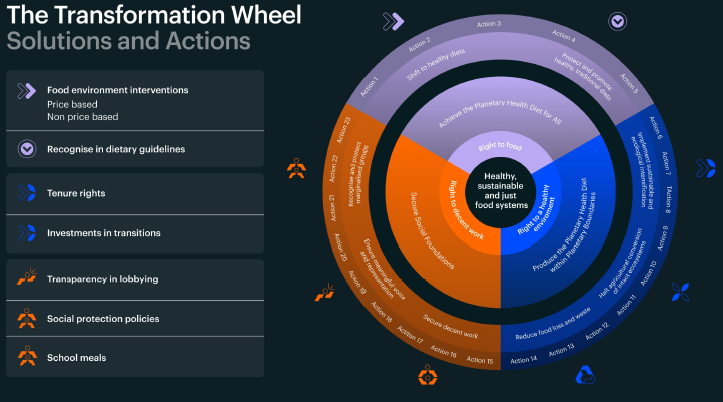

What does this all mean for action?

The urgency and the ambition that is required in order to bend the curves is significant. The report spells out not only what people should eat, but also what must happen across food systems (production, distribution, procurement, policy) to enable this shift.

There is a critical need, particularly for all countries, to develop food system pathways that integrate across these multiple goals and collaborate between countries to understand what the collective impact is and to recognise fair shares in the transition to healthy, safe and just food systems.

Eight domain-specific solutions with 23 associated actions, designed to advance health, environment and justice goals were highlighted.

The solutions suggested are:

-

Protect and promote traditional healthy diets

-

Create accessible and affordable food environments that increase demand for healthy diets

-

Implement sustainable production practices that store carbon, create habitats and improve water quality and availability

-

Halt agricultural conversion of intact ecosystems

-

Reduce food loss and waste

-

Secure decent working conditions across the food system

-

Ensure meaningful voice and representation for food systems workers

-

Recognise and protect marginalised groups

The transformation section of the report highlights a specific need to bundle policies, recognise context and also ensure that solutions are rooted in local context based on local needs, adapted to local capabilities and by using local knowledge.

Diverse communities for action, cutting across chefs, restaurants, food service, consumers, indigenous peoples, storytellers, manufacturers and beyond can together collaborate to unlock potential and collectively drive change.

Considered by the commission as key changemakers healthcare professionals are being called upon to support this transition alongside the other communities for action. In partnership with EAT, PAN International convened the Healthcare Professionals Community for Action dialogues, representing 72 organisations worldwide, to translate the PHD into practical, health sector-specific actions. The Action Brief for Healthcare Professionals, which includes stories of progress, can be downloaded.3 This is just the beginning, and many more will be added.

Implications for dietitians, healthcare professionals and food system actors

Here are some key implications for dietitians, organised by level of action.

1. Clinical/dietetic practice

-

Educate dietitians and health professionals on the science and practice of healthy sustainable diets

-

Educate patients/clients about the ‘plant-rich, mostly whole-food’ pattern, emphasising legumes, nuts, whole grains, vegetables and fruits in the context of both health and environment

-

Use the quantitative intake targets to inform meal planning, counselling, food service design (for example in hospitals and schools) and communicate that reducing red and processed meats and limiting saturated fat, sugar and salt is part of a broader health-and-planet agenda

-

Recognise that for some populations (e.g. older adults, pregnant women, low-income settings) there may be risk of nutrient gaps (e.g. B12, iron, iodine) and advise accordingly.

-

Be a translator of systems thinking: link individual eating behaviours with service-level and policy-level levers (procurement, institutional food, community nutrition). For example, hospital catering or workplace catering can be aligned with the flexible reference diet

-

Monitor and address potential unintended consequences: cost/affordability, food culture, acceptability and nutrient adequacy for some vulnerable groups. Equity and justice are central – so dietitians should advocate for accessibility and affordability of healthy and sustainable diets for all

2. Institutional/service level (foodservice, procurement, catering, public health)

-

Re-design menus, procurement practices and food service design using the flexible reference diet as a framework, e.g. increasing legumes/nuts, reducing red meat servings, increasing vegetable-rich dishes, choosing whole grains, including plant protein options.

-

Integrate sustainability metrics into menu planning (e.g. using more plant-based-protein dishes, reducing food waste, sourcing sustainably produced foods), aligned with the commission’s systems dimension

-

Monitor affordability and access: the report emphasises that healthy sustainable diets must be accessible and affordable to everyone

-

Collaborate across supply chain: link with farmers, producers and suppliers to increase supply of legumes, nuts and diverse crops and reduce reliance on resource-intensive meats

-

Use institutional leverage: schools, hospitals and universities can act as demonstrators of healthy, sustainable, equitable food systems

-

Embed evaluation: track health outcomes, environmental impact (e.g. greenhouse gas footprint) and equity metrics (accessibility for low-income groups) to support continuous improvement and publish results to help share learnings with others

3. Policy and advocacy level

-

Key policy levers include: shifting subsidies from intensive foods (e.g. beef) towards healthy sustainable foods (fruits, legumes, nuts), regulating marketing of unhealthy foods, pricing mechanisms (taxes on high-impact foods, subsidies on healthy ones), investing in research/innovation for more sustainable agriculture

-

Integrating sustainable healthy diet targets into national dietary guidelines, food system strategies and climate/land-use policies

-

Ensuring that justice dimensions (fair working conditions in food systems, rights of marginalised groups, inclusive voices in food system governance) are embedded in every stage of transformation

-

Framing the shift as win-win-win (health + environment + equity) helps build broader coalitions: healthcare, agriculture, environment, labour

-

Monitoring and accountability: setting metrics for diet, production, planetary boundaries and justice outcomes. Tracking progress is essential

In conclusion

The 2025 EAT-Lancet Commission report provides a landmark update in the field: it brings together health, environment and justice in one integrated framework and gives a clear but flexible reference diet (PHD) alongside systems-level levers for urgent action and transformation.

Dietitians have an opportunity to contribute and collaborate for institutional food environment change, procurement/design of services and advocacy for policy change (especially around access, affordability and equity). We can utilise the PHD as a lever to engage multi-disciplinary collaborators (agriculture, supply chain, environment, public health, community development) in order to deliver transformational change.

As dietitians, we are well positioned to translate the evidence into practice, guide individual and food environment change, and advocate for systemic action that supports healthy, sustainable and just food systems for all.

References

- Rockström, J. et al. The EAT–Lancet commission on healthy, sustainable, and just food systems. The Lancet 406, 1625–1700 (2025). https://www.theLancet.com/journals/Lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(25)01201-2/abstract

- Action Brief for Healthcare Professionals https://eatforum.org/publication/eat-Lancetcommission-brief-for-healthcareprofessionals/ (2025)

- EAT Communities for Action https://eatforum.org/publications/ (2025)

- Afshin, A. et al. Health effects of dietary risks in 195 countries, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. The Lancet 393, 1958–1972 (2019). https://www.theLancet.com/article/S0140-6736(19)30041-8/fulltext

- Willett, W. et al. The Lancet commissions Food in the Anthropocene: the EAT-Lancet commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems Executive summary. The Lancet 393, 447–492 (2019). https://www.theLancet.com/journals/Lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(18)31788-4/abstract

- One Health https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/one-health (2021)

- Office for Health Economics (OHE) https://www.ohe.org/news/a-switch-to-vegan-dietscould-save-the-nhs-6-7-billionper-year-new-research-reveals/ (2024)